![]()

![]()

THE DEATH OF TUTANKHAMUN

Appendix to TUTANKHAMUN: THE EXODUS CONSPIRACY

by

Andrew Collins and Chris Ogilvie-Herald

In his

international bestseller The Murder of Tutankhamun, first published

in 1998, paleopathologist Bob Brier accuses Aye, Tutankhamun's vizier

and administrator, of assassinating the boy-king. This conclusion was

reached after he examined forensic evidence derived from the pathological

studies of Tutankhamun's remains conducted by Professor Ronald G. Harrison

of the University of Liverpool.

After

scholarly requests to examine the mummified body, Harrison was finally

granted permission by the Egyptian authorities to X-ray the boy-king

in 1968. Since its earlier examination by Dr Douglas E. Derry, the Professor

of Anatomy at the Egyptian University, Cairo, in 1925, the skeleton

had rested in one of the gilded coffins re-interred inside the great

quartzite sarcophagus left in situ within the tomb.

Working alongside a specialised team which included experienced radiologists, physicians, dentists and Egyptologists, Harrison was allowed to expose the pathetic remains of the king for just two days only. What they found shocked them, for there was considerable damage to the skeleton never officially recorded by Carter and Derry. Harrison even found that the body had been sawn in half in order to free it from the innermost coffin. Yet this realisation simply enabled Harrison to carry the head, and other body parts, over to the machine and photograph them individually. The team was only allowed to carry out their work in daylight hours, and the X-rays taken were carefully transported back to Luxor where they were developed in one of the rooms of the Winter Palace Hotel, rented for this purpose.

|

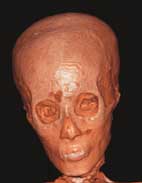

Tut's cranium. |

When published for the first time, the X-rays taken of the skull caused a sensation, for they showed that a small fragment of bone was lodged within its interior, fuelling the theory that Tutankhamun might have died from a blow to the head, received either accidentally or as a result of foul play. Harrison attempted to play down the significance of the tiny bone by pointing out that it had probably become dislodged from the base of the nose during the post-mortem embalming process. Yet Bob Brier doubted this solution, pointing out that a nasal bone of the sort indicated by Harrison was porous and splintered when broken, while the one inside Tutankhamun's skull was more substantial in size. Brier went on to conclude that it had broken away from the inside of the skull during Carter and Derry's quite violent stripping of the mummy back in 1925. |

This was important, for a number of Egyptologists had continually cited the mistaken way in which some speculative writers wrongly used the presence of the small bone as evidence of Tutankhamun's death. Yet as Brier pointed out, the bone fragment was a 'red herring', diverting the eyes away from the real evidence that the boy-king had suffered severe internal injuries after a major blow to the head.

Was

it Murder?

Bob Brier's initial clue that foul play might have been involved in

the death of the pharaoh came as he watched a BBC documentary in which

Professor Harrison was asked to comment on his findings concerning the

X-rayed skull of Tutankhamun. During the interview, he pointed out the

presence at the base of the head, close to the neck, of an inexplicable

'density', or dark area, before adding that in his opinion:

This is within the normal limits [of skull growth], but in fact, it could have been caused by a hemorrhage under the membranes overlaying the brain in this region. And this could have been caused by a blow to the back of the head and this in turn could have been responsible for death.

What

exactly was this dark area, or 'density', at the bottom of the skull,

and how might it have been the result of 'a blow to the back of the

head'? Among those consulted by Brier in an attempt to find some answers

was Dr Gerald Irwin, medical director of the Radiologic Technology Program

at the C. W. Post Campus of Long Island University, and an expert on

the X-rays of head trauma patients. Having been shown the Harrison video,

Dr Irwin examined an X-ray photograph of Tutankhamun's skull sent to

Brier by one of Harrison's former colleagues at Liverpool University,

who has since died. In conclusion, Irwin agreed that the dark area (as

well as a thinning of the skull at this point) could easily have been

the result of a blow to the back of the head. Furthermore, he speculated

that this type of trauma, or effect, was, as Harrison had hinted, strong

evidence of a haematoma, the accumulation of blood beneath the skin.

The density could thus be explained in terms of a calcified membrane

which had grown over a blood clot, something physicians refer to as

chronic subdural haematoma, a swelling caused by blood.

Irwin

commented also on the strange position of the trauma which was at the

base of the head, where the neck joins the skull. If Tutankhamun had

been struck purposefully then it must have occurred when he was either

lying on his stomach or on his side. Brier concluded that although the

evidence presented by the X-ray was not proof of foul play, it added

up to what the police might argue was an 'indication of suspicious circumstances'.

So is

this what happened to Tutankhamun? Was he perhaps bludgeoned whilst

asleep in bed, leaving him to die a slow painful death as he lay in

a delirious state waiting for the end to come? Certainly, this is what

Bob Brier believes, and he could well be right for the evidence to suggest

that the boy-king did indeed die from a blow to the head is very powerful

indeed. But was it foul play? Was somebody responsible for his death?

The

true answer is that nobody knows. The only evidence we have for the

involvement of foul play in the boy-king's death derives from personal

interpretations of the Harrison X-ray made in 1968 and what little we

know about the life of Tutankhamun. It is just as likely that he sustained

his wound through accidental means. For example, falling backwards awkwardly

can result very easily in blows to the base of the skull. Thus he could

easily have been thrown backwards out of his chariot and knocked his

head on a rock, or some other similar such protrusion. There is no reason

to assume murder took place just because of the peculiar positioning

of the trauma. Then there is the problem of why the would-be assassin

did not complete the job. If he, or she, had bludgeoned the king whilst

asleep, why not finish him off there and then, either with repeated

blows or by strangling him whilst he lay unconscious. Surely, the person,

or persons, responsible would not have assumed that the king was dead

simply by giving him one single blow to the head. Logically, this makes

no sense whatsoever.

Even

if murder is the answer, Bob Brier's choice of Aye as the murderer seems

totally illogical. According to him, the only other candidate was Horemheb,

the king's Deputy and Regent, who took charge of military and political

affairs from Memphis, Egypt's administrative centre, and if he had done

the dirty deed then nothing would have prevented him from seizing the

throne of Egypt. Thus by default the only other possible candidate was

Aye who, as we know, succeeded Tutankhamun as king of Egypt. In the

opinion of the authors, this theory is baffling in the extreme, for

the evidence weighs heavily against it.

Following Tutankhamun's sudden and presumably unexpected death, it was Aye, the old family retainer, who was left to make the arrangements for the funeral. This we know is correct because Aye is depicted on the wall of the tomb wearing the leopard skin of the setem-priest. He stands before the mummified body of Tutankhamun in his guise as Osiris, god of the underworld, holding an adze and carrying out the Opening of the Mouth ceremony. In this capacity Aye takes the role of Horus, the 'son' of Osiris, reviving his spiritual 'father', an act conducted only by the heir apparent. This mural demonstrates also that Aye was decreed honorary heir to the throne of Egypt, and thus was responsible for conducting the various rites of passage that would enable the boy-king to enter the next world.

Worship

of the Aten

Then we come to the presence in the tomb of various personal items that

either depict the Aten sun-disk in all its glory or bear inscriptions

which include the name of the Aten, some nine years after Tutankhamun

is supposed to have abandoned all interest in Akhenaten's hated religion.

By far the best example is the famous gilded throne chair found in the

Antechamber. On the inside of the backrest we see the king seated, with

his young queen standing before him, equal in height. In her left hand

she holds an offering cup of balm, or oil, and with the other she is

seen touching his shoulder in a most tender fashion. Both king and queen

are portrayed in typical Amarna style, but more significantly we see

the Aten sun-disk, with its rays ending in hands that offer life in

the form of ankhs, directly above the young couple. Moreover, the name

of the king appears both in its later form of Tutankhamun and its Amarna

form of Tutankhaten.

Since

this beautiful work of art was deemed suitable to accompany the pharaoh

on his journey into the next world, it seems clear that Tutankhamun,

as well as his wife Ankhesenamun, must have remained sympathetic towards

the outlawed religion, even at the very end of his reign. Moreover,

since we know that Aye was almost certainly responsible for making the

king's funeral arrangements, he would have been aware that various items

of Amarna art were being placed in the tomb, demonstrating that he too

retained at least some sympathies towards the Aten. This realisation

implies very strongly that Ankhesenamun and Aye were working in concert,

and were not opposed to each other's religious or political ideals.

Having

established these facts, we come now to a matter crucial to this debate,

the correspondence between Ankhesenamun and Suppiluliumas, the king

of the Hittites, following the death of Tutankhamun. In the knowledge

that there was no heir to the throne, she feared a military cue, an

uprising, from those who sought to take away her power and influence.

It forced her into a decision unprecedented in Egyptian history. In

order to try and find a suitable partner, who would rule the kingdom

with an iron fist comparable with that of the greatest of pharaohs,

she sent a letter to Suppiluliumas beseeching him to send her a son

so that he might become Pharaoh. At first he was suspicious of the request,

but eventually he relented and dispatched a young prince named Zannanza,

who was mysteriously murdered en route from the land of Hatti, i.e.

Turkey, to Egypt.

In her

original message to Suppiluliumas, she tells him that: 'Never shall

I pick out a servant of mine and make him my husband!' Who exactly might

she have been referring to when she made this powerful statement? Aye

had been an important member of the royal court at Amarna during Akhenaten's

reign. He took the title Master of the Horse, which in effect meant

that he was a military adviser and vizier to the king. Yet in inscriptions

he also styled himself 'Father of the God', a title he kept from the

reign of Akhenaten through to his own brief four-year reign. By 'God'

he meant god-king, or pharaoh, implying that he was a relative, or in-law,

of Akhenaten. The same title, 'Father of the God', was used by Yuya,

the father of Tiye, the Great Royal Wife of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten's

father. Thus Aye was most probably related to the heretic king, and

it has been proposed that he was probably the father of Nefertiti. Since

Aye was regarded therefore as a member of the royal household, Ankhesenamun

can hardly have been referring to him as a 'servant of mine', in other

words a commoner.

So who had she been referring to in the plea to the Hittite king?

Ankhesenamun's

statement refers most likely to Horemheb who was devoid of any royal

blood, or royal connections. He is the only other suspect in the hunt

to find the hypothetical killer of Tutankhamun. As a military genius

he had quite obviously set his sights on becoming king at a very early

stage in the Amarna heresy, and quite probably he worked in concert

with the disbanded Amun priesthood, as well as other army officials,

to achieve his aims. If this is correct, then the sheer fact that Horemheb

did not ascend to the throne after the death of Tutankhamun, makes it

even more unlikely that the boy-king was assassinated. For if Horemheb

was responsible for his murder, then Aye would never have become king;

it is as simple as that.

With these thoughts as a backdrop to the death of Tutankhamun, we can now better understand why Ankhesenamun dispatched amessage to the Hittite king asking him for a husband. Quite obviously, she had been faced with the prospect that since the couple had produced no heir, there was no one to succeed her husband to the throne. She therefore feared that Horemheb was plotting to seize the throne by initiating a military coup and forcing her to marry him in order to legitimise his reign. In fear, she pleaded with the Hittite king to send her a son, only to find that the young prince was assassinated on his way to Egypt. With time running out for the frightened queen, she honoured Aye with the title of king of Egypt in order to block Horemheb's intentions.

A

Hunting Accident?

So how exactly did Tutankhamun die? Since it is noted that the boy-king

was a keen hunter, there is every possibility that, whilst on a hunting

expedition, he fell awkwardly from his chariot and sustained a blow

to the head that eventually proved fatal. Remember, he was only around

18 years of age when he died, and may not have been as experienced in

this pursuit as he might have thought. We must also not confine the

accident to a hunting expedition, for it could have occurred at any

time that he was in motion on a chariot.

When his skull was examined originally by Carter and Derry in 1925 it was found to have been shaved, an uncommon practice for a dead king. Can we imagine, therefore, the physicians of the royal court removing the king's hair in order to determine the nature of the swelling, which would have occurred in the weeks that followed the initial blow to the head? Thus having found no external evidence of a wound, there would have been little they could have done to alleviate the swelling, leaving the king to suffer ever-worsening headaches and black outs as the haematoma gained ground. Finally, he would have fallen into a coma before losing his fight for life. Since calcification occurred around the swelling, it points towards the fact that Tutankhamun must have lived for a minimum of two months after the blow, and conceivably up to several months before death eventually overcame him.

Pharaohs'

Fall

Where does this vivid picture of the dramatic events which would seem

to have occurred at the end of Tutankhamun's reign leave us with respect

to the relationship between the Amarna period and the biblical Exodus,

which seems so obviously linked with the Amarna aftermath?

The answer is this: as early as 1923, even before Carter and Derry's examination of the mummified remains of Tutankhamun, British Egyptologist Arthur Weigall in his book Tutankhamen and Other Essays, highlighted a curious story in the Talmud, the literary corpus containing the folklore of the Jews. It echoes the violent manner in which Tutankhamun seems to have died, and yet concerns the fate of the pharaoh said to have ruled Egypt at the time when Moses left Goshen for the land of Midian, having slayed an Egyptian official whom he found maltreating an Israelite. According to the legend, at this time Pharaoh was struck down with leprosy (an allusion, perhaps, to the fact that he was infected by the much shunned Aten heresy). Moreover:

While he was in this agony [with leprosy], the report was brought to him that the children of Israel in Goshen were careless and idle in their forced labor. The news aggravated his suffering, and he said: 'Now that I am ill, they turn and scoff at me. Harness my chariot, and I will betake myself to Goshen, and see the derision wherewith the children of Israel deride me.' And they took and put him upon a horse, for he was not able to mount it himself. When he and his men had come to the border between Egypt and Goshen, the king's steed passed into a narrow place. The other horses, running rapidly through the pass, pressed upon each other until the king's horse fell while he sate upon it, and when it fell, the chariot turned over on his face, and also the horse lay upon him. The king's flesh was torn from him… [and his] servants carried him upon their shoulders, brought him back to Egypt, and placed him on his bed.

He knew that his end was come to die, and the queen Alfar'anit and his nobles gathered about his bed, and they wept a great weeping with him.

Could it be possible that preserved among the folklore of the Jews is a dim recollection of the fall which led to the death of Tutankhamun? If so, did the boy-king fall from a horse, as is suggested here, or from his chariot? Some confusion might well have entered the story when still an oral tradition among the ancestors of the Jewish peoples since pharaohs usually rode in chariots, and not on horseback. Although there are other elements in the Talmud legend that do not make sense of what we know about the boy-king, a connection with the reign of Tutankhamun cannot be ruled out. Weigall himself was of the opinion that the Pharaoh in question was none other than Akhenaten, due to the clear relationship between the Amarna regime and Manetho's Osarsiph-Moses story and the fact that the Talmud asserts that the king produced so many offspring ('He had three sons and two daughters by the queen Alfar'anit, besides children from concubines' ). However, Weigall would surely have switched his focus of attention to Tutankhamun if he had lived to see the X-ray of the boy-king's skull produced in 1968 by Professor Harrison. Such evidence weighs heavily against Bob Brier's belief that Tutankhamun was murdered in his sleep by the orders of Aye, a theory which holds no weight whatsoever.

All references to this article are to be found in TUTANKHAMUN: THE EXODUS CONSPIRACY by Andrew Collins and Chris Ogilvie Herald. Signed copies by Andrew Collins can be obtained by clicking here.

![]()