![]()

![]()

Göbekli

Tepe and the Worship of the Stars: A Question of Orientation

A Mandaean ceremony that took place on the banks of the Euphrates river in the late nineteenth century provides compelling evidence that the early Neolithic cult sanctuaries of Göbekli Tepe were orientated towards the north, and not towards the south, the direction of the dog-star Sirius

A

Report by Andrew Collins

For a PDF of this article click here

Italian

archaeoastronomer Giulio Magli proposes

that key sanctuaries at Göbekli Tepe are aligned to the rising of Sirius,

c. 9100-8250 BC (Magli, 2013). His theories have received support from New Scientist

magazine, which published a feature on the subject under the headline "world's

oldest temple built to worship the Dog Star" (Ananthaswamy, 2013).

Yet

as pointed out by chartered engineer Rodney Hale and the author in a detailed

response to Magli's proposal (Collins & Hale, 2013), there are severe problems

in accepting Sirius's role at Göbekli Tepe, due to its feeble motion and

poor visibility at the time. Indeed, for hundreds of years after its reappearance

on the southern horizon in c. 9500 BC (having been invisible from the latitude

of Göbekli Tepe for as much as 5,500 years), it would barely have lifted

off the horizon, making it unlikely that in order to venerate this long lost star

the Proto-Neolithic hunter-gatherers of southeast Anatolia (Asiatic Turkey) abandoned

their cherished lifestyle to create the first monumental architecture in human

history.

Rodney

Hale, who has worked extensively in the field of archaeoastronomy for 15 years,

has written a letter to the editor of the New Scientist pointing out the main

criticisms of Magli's theory,1 although whether they see fit to publish it is

quite another thing.

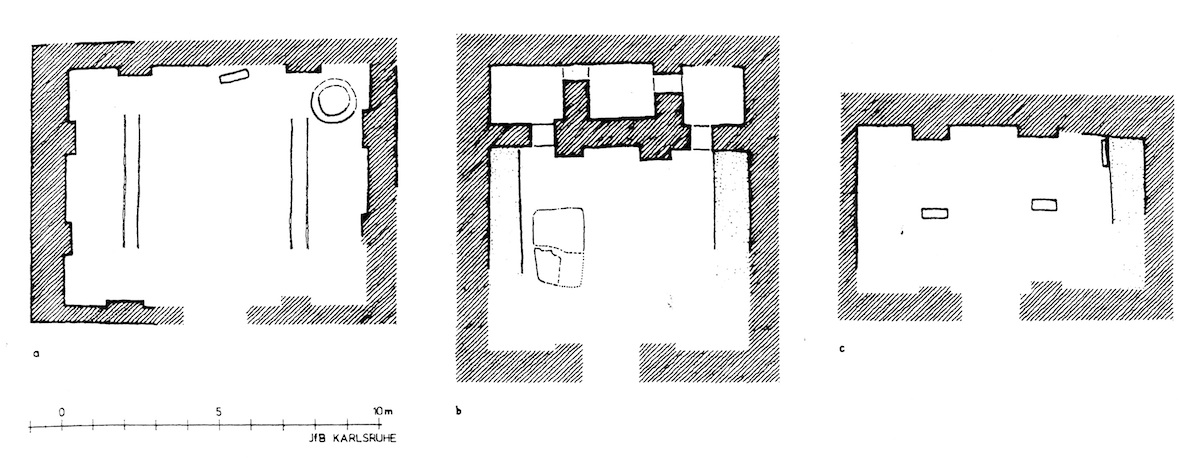

Beyond these problems is the fact that there is overwhelming evidence that the peoples of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic age in southeast Anatolia oriented their buildings not towards the south, the direction of Sirius, but to the north, the direction of the celestial pole and the circumpolar stars (Collins, 2006, 2013, 2014; Collins & Hale, 2013). Their cult buildings, shrines and sanctuaries are invariably built with entrances to the south, with evidence of ritual activity taking place in the north. This can be seen not only at Göbekli Tepe, but also at sites such as Nevali Çori, Hallan Çemi and particularly at Çayönü (Schirmer, 1990). This realization brings the orientation of these buildings in line with the direction of prayer of religious sects that once thrived in the same region, and may well owe at least some of their beliefs and practices to the Neolithic age.

The

City of Harran

They

include the inhabitants of Harran, the ancient city on the Harran plain, just

41km (25.5 miles) south-southeast of Göbekli Tepe. From the Bronze Age, c.

2200 BC, down to medieval times the Harranites venerated the deities of the Babylonian

and Assyrian pantheons, with the moon-god Sin and his consort Ningal being the

city's primary deities. Much later they adopted aspects of Neo-Platonism, Persian

Magism, and even Hebrew mythology, believing themselves to be descended from the

patriarch Abraham. He and his father even had their own temple at Harran (Lloyd

and Brice, 1951).

The Bronze Age city at Harran almost certainly superseded a much earlier Neolithic settlement located on the same site. Excavations since 2005 at a nearby mound named Tell Idris (the Hill of Idris, the Arab name for both the Greek god Hermes and the patriarch Enoch) have revealed a series of occupational layers going back to the Neolithic age, c. 8000-6000 BC (Yardimci, 2008, 362-364). These are overlaid by occupational levels belonging to the Halaf culture, c. 6000-5000 BC, and the Ubaid culture, c. 5000-4100 BC, showing a continuous occupation of nearly 4,000 years. Tell Idris was the first place inhabited in the Harran district. Yet following its abandonment, the population shifted their attentions to Harran itself, which now became the main occupation site, even though it had existed in its own right since the Halaf period.2

Sabaean

Star-worshippers

It

is extremely possible that aspects of the beliefs and practices expressed by the

Göbekli builders persisted in the region and eventually found their way into

the religion of the Harranites, who from the ninth century onwards were known

as Sabaeans, from the Arabic saba'a, meaning "to change, to come out, to

convert, to return". Various medieval Arab writers visited Harran and wrote

about the strange and highly exotic religion of the Sabaean star-worshippers,

which revolved around a personification of the sun, moon and planets as angels

or spirit intelligences. Their chosen qibla, or direction of prayer, was said

to have been the north,3 the direction of the Pole Star, and every year the "Mystery

of the North" was celebrated with a grand festival.4

The

Harranites' obsession with the north as the direction of the Primal Cause was

something inherited by their latter day descendants the Mandaeans, who, like the

Harranites, are referred to as both Sabaeans and star-worshippers. Known also

as the Subba, Manday, Nazoreans, and even St John's Christians, due to their veneration

of John the Baptist (although not Jesus), the Mandaeans are found mostly in small

pockets along the Euphrates river in South Iraq. However, their original homeland

was much further away, either in the Transjordan and/or around the area of Harran,

which features by name in their foundation texts. Almost certainly they are related

to the Harranites, who were forced to disperse following the destruction of Harran

by the Mongols in 1251.5

The

Mandaeans practice a complex blend of Magian angelology, Gnostic Christianity,

and Babylonian astrology involving the seven planets and the twelve signs of the

zodiac. Like their forerunners the Harranites, the Mandaeans venerate the Pole

Star, which they see as a visible manifestation of the Supreme Being, as well

as the access point to the abode of the righteous, and the destination of the

pious in death. Offerings are made to the north, while the dead are buried with

their feet in the north and their heads in the south, so "that the north

star (i.e. the Pole Star) may be in front of the eyes", since the north is

"the abode of Avather (the angel of the scales, judge of the dead and guardian

of paradise) and there, too, is Olmi-Danhuro (paradise)".6

That a link existed between the Harranites' and Mandaeans' veneration of the Pole Star and the beliefs and practices associated with the sanctuaries at Göbekli Tepe is tantalizing. This seems especially so in the knowledge that other religious groups that once thrived in the region also saw the north as the principal direction of prayer. They include the angel-worshipping Yezidi, who once thrived in SE Turkey, and the Shi'ite sect known as the Isma'ili Brethren of Purity (Ikhwan al-Safa'), whose centre was at Bosra in Syria (Collins, 2006). Yet can we take the matter further?

Festival

of the Pole Star

The

answer is yes, for I have come across a remarkable account of a new year festival

conducted by the Mandaeans on the banks of the Euphrates river in the late nineteenth

century that throws considerable new light on the subject. It highlights the sect's

absolute veneration of the Pole Star, which is described as "Olma d'nhoora,

'the world of light', Dayan-samê, 'The Judge-of-heaven'", and also

as the "primitive sun of the Star-worshippers' theogony, the paradise of

the elect, and the abode of the pious hereafter'. Significantly, the account-published

in the London Standard of 19th October, 1894 under the headline "A Prayer

Meeting of the Star Worshippers", and later included in Robert Brown's Researches

into the Origin of the Primitive Constellations of the Greeks, Phoenicians and

Babylonians (Brown, 1900, 177-179)-provides a vivid picture of the construction

and use of a cult hut called the "Mishkna", referred to also as the

bit manda or bit mashkna. This, as we shall see, bears striking similarities to

the layout of early Neolithic cult buildings, including those at Göbekli

Tepe and Çayönü, located around 160km (100 miles) north-northeast

of Harran.

The location of the new year festival is given as Sook-es-Shookh (modern Suq al-Shuyukh), a small township near the city of Basra in what is today southern Iraq. The date is presumably 1894, with the time of year being "late September". I will let the narrator take up the story (with some paraphrasing from Robert Brown):

'The stars are beginning to twinkle overhead, but there is still sufficient light to note the strange white-robed figures moving stealthily about in the semi-gloom down by the river side … "Their fathers were burned," cries our Persian guide in disgust . . . thus delicately hinting that they are not followers of Islam; and a Jew who accompanies our party, on his way to the tomb of Ezekiel, spits upon the ground, and exclaims in pure Hebrew, Obde kokhabim umazaloth' ['Servants of the stars and Signs of the Zodiac'].

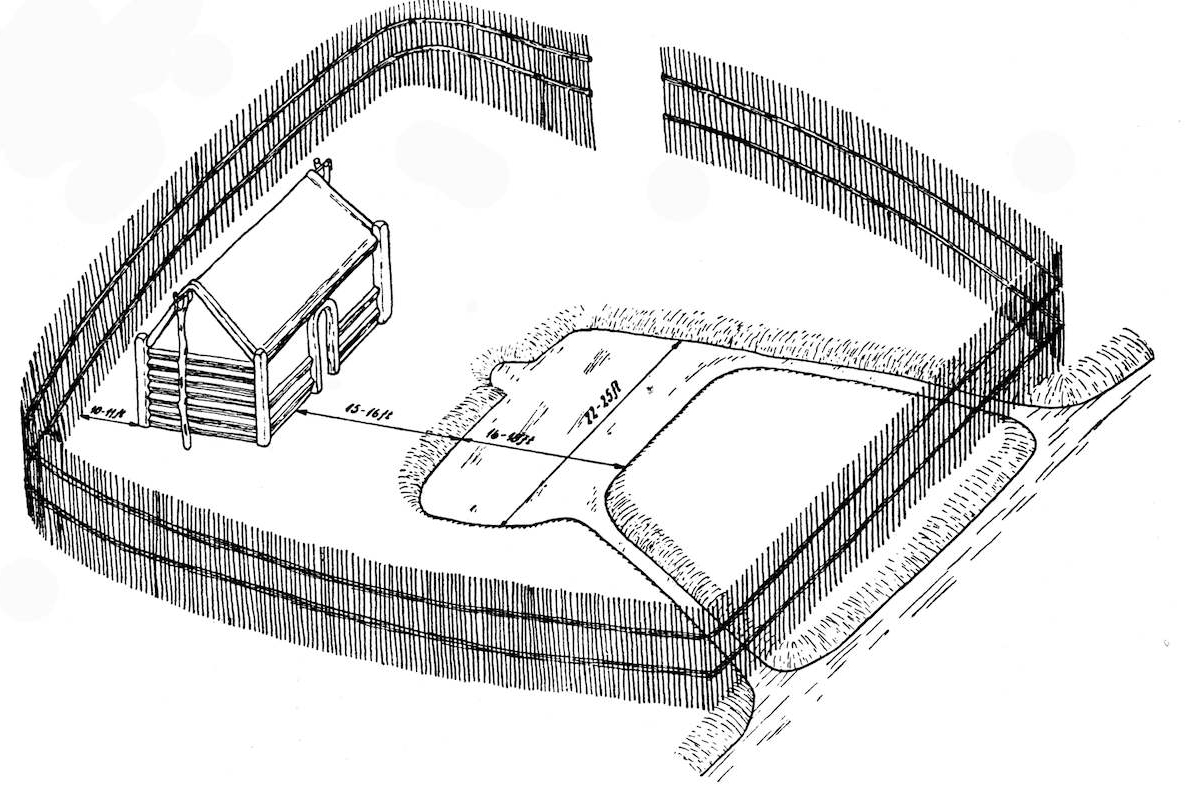

When we first meet them the white-robed Mandaeans are in the process of completing the Mishkna, or 'tabernacle', which will play a crucial role in the upcoming "grand annual festival":

An oblong space is marked out, about 16 feet long and 12 feet broad by stouter reeds, which are driven firmly into the ground close together, and then tied with strong cord. To these the squares of woven reeds and wattles are securely attached forming the outer containing walls of the tabernacle. The side walls run from north to south, and are not more than 7 feet high. Two windows, or rather openings for windows, are left east and west, and space for a door is made on the southern side, so that the priest when entering the edifice has the North Star, the great object of their adoration, immediately facing him. An altar of beaten earth is raised in the centre of the reed-encircled enclosure, and the interstices of the walls well daubed with clay and soft earth, which speedily hardens.

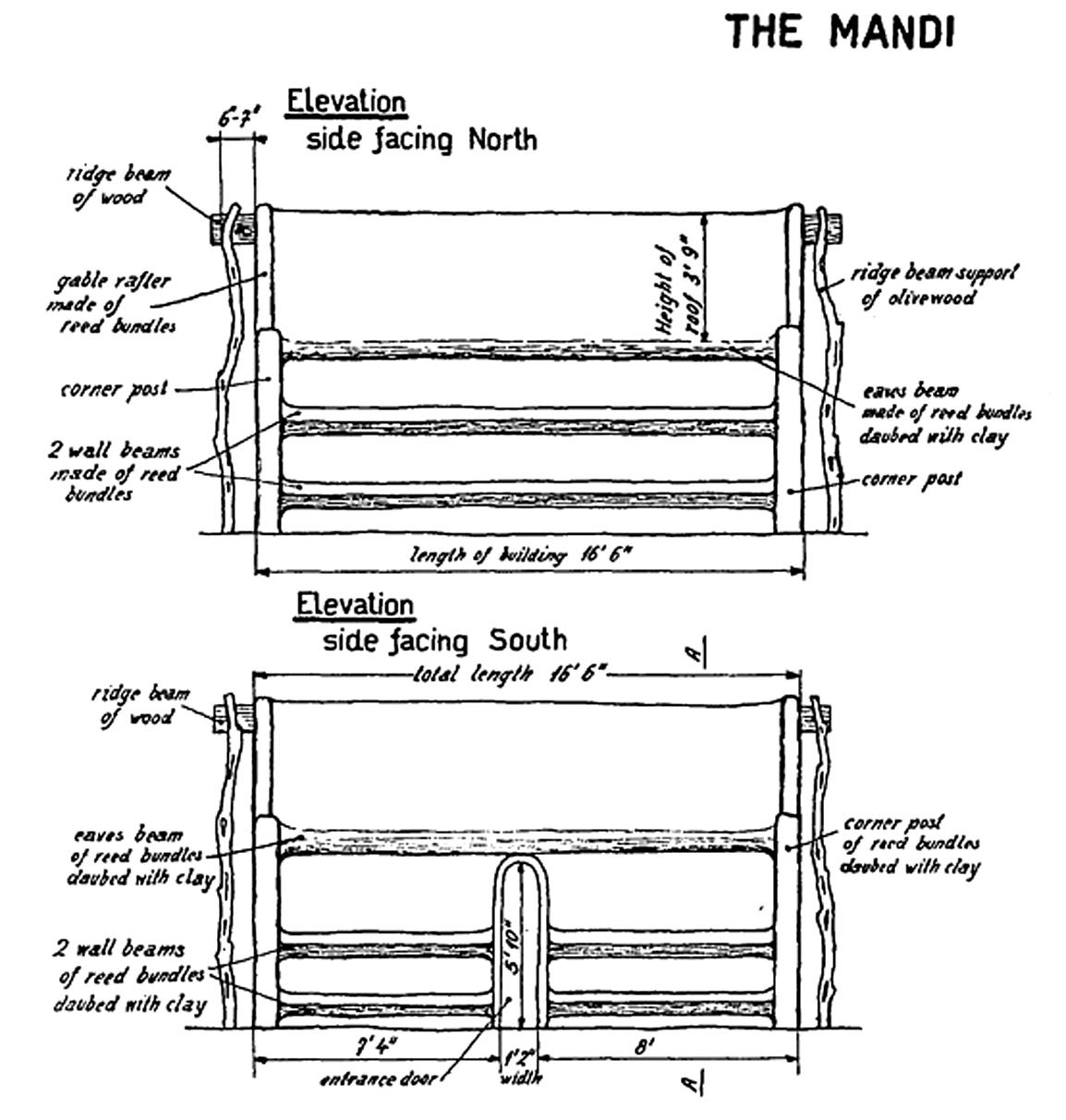

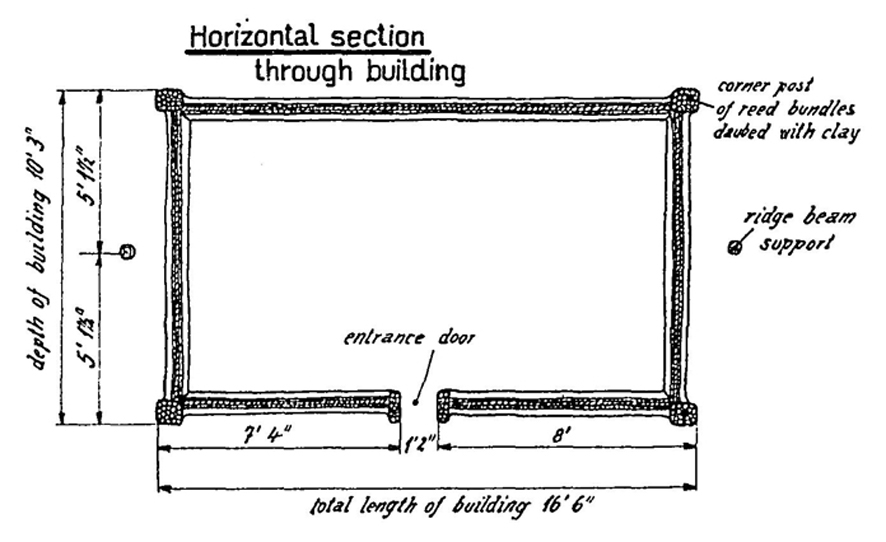

Although

not made clear, the Mishkna's two longest sides are aligned east-west (see Figs.

1, 2, 3 & 5). The windows are placed in the two narrow walls, aligned north-south.

White curtains are placed over the windows, although the structure itself remains

open to the sky.

The

Mishkna's entrance is created midway along the southern wall, exactly like the

Pre-Pottery Neolithic cult buildings. Indeed, the shape, layout and orientation

of the Mishkna greatly resembles the cult buildings at Çayönü,

two of which (the Terrazzo Building and Flagstone Building) also have wider east-west

aligned walls with south-facing doorways (see Fig. 4). As we shall see, the express

purpose of the Mishkna's southerly placed entrance is in order for the Ganzivro,

the spiritual head of the sect, to fix his gaze on the Pole Star as he enters

the tabernacle.

Two smaller cubicles, just big enough to hold a single person, are then constructed of reeds immediately beyond the cult hut's south wall. One cubicle is reserved for the use of the Ganzivro, and once completed no one other than him is allowed to even touch its walls. A circular baptismal pool is also created close to the southern entrance. This is filled with water channeled directly from the river (see Fig. 1).

Mandaeans

arriving for the festival use the second cubicle to disrobe before plunging themselves

into the baptismal pool, an act presided over by a tarmido priest who pronounces

a blessing as the immersion takes place. Thereafter each person covers themselves

in clean white garments, which reach almost to the ground.

As the night progresses

around twenty rows of white-robed figures, all ranked in an orderly array, gather

on the riverside. They sit patiently facing the Mishkna awaiting the arrival of

the priests who will conduct the much anticipated ceremony. Two guards stand by

the entrance:

… (they) keep their eyes fixed upon the pointers of the Great Bear. As soon as these attain the position indicating midnight.' a signal is given, and a procession of priests, including … the Ganzivro moves to the Mishkna. One 'deacon' 'holds aloft the large wooden tau-cross.' A second bears 'the sacred scriptures of the Star-worshippers.' A third 'carries two live pigeons in a cage,' and a fourth has 'a measure of barley and of sesame seeds.'

So

not only does the Pole Star feature in the ceremony, but the stars making up the

Big Dipper or Plough in the constellation of Ursa Major, the Great Bear, are watched

in order to mark the moment of midnight. In many ancient cultures, the seven main

stars of Ursa Major were seen as the turning mechanism of the heavens, as well

as time-keeping devices for those engaged in nocturnal activities.

Returning

to the account of the Mandaean new year festival, we read that:

The ecclesiastics file into the Mishkna, and stand 'to right and left, leaving the Ganzivro standing alone in the centre, in front of the earthen altar facing the North Star, Polaris. The sacred book Sidra Rabba is laid upon the altar folded back where the liturgy of the living is divided from the ritual of the dead. The high priest takes a live pigeon, 'extends his hands towards the Polar Star, upon which he fixes his eyes, and lets the bird fly, calling aloud, "In the name of the living one, blessed be the primitive light, the ancient light, the Divinity self-created."'

Here

the Ganzivro approaches the Mishkna's earthen altar after entering the structure

from the south. Once again this brings to mind the layout of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic

structures of southeast Turkey, whose own southerly placed entrances perhaps played

a similar role, enabling the priest or shaman to face an object of veneration

in the northern night sky. The centrally positioned altar in the Mishkna takes

the place of the twin central pillars seen in the principal enclosures at Göbekli

Tepe, and the twin standing stones erected side-by-side at the centre of two of

the cult buildings at Çayönü (the Flagstone Building and Skull

Building).

The Mishkna has no roof and remains open to the sky in order for the Ganzivro to gaze upon the Pole Star. Yet whether or not the early Neolithic sanctuaries at places like Göbekli Tepe and Çayönü possessed roofs remains a matter of debate. From the marks, cuts and grooves on the top of certain pillars in Göbekli's Enclosure C (See Fig. 6) this does seem likely, although perhaps a roof was used either partially or at certain times of the year.

Soul

Birds and Excarnation

The

Ganzivro's release of the pigeon towards the north is also significant. Arguably,

it is a metaphor for the release of the soul in death in order for it to journey

to the North Star, the entrance to the abode of the dead in Mandaean tradition.

Such an act might easily reflect the ritual processes behind the act of excarnation,

where human carcasses are exposed to vultures and other carrion birds before the

bones are collected up for a so-called secondary or disarticulated burial.

Excarnation

is known to have been important to early Neolithic communities in central and

eastern Anatolia, and is even depicted on the walls at Çatal Höyük,

the 9,000-year-old Neolithic city on the Konya plain in southern central Turkey.

In this manner, the vulture, and thus the bird in general, became the primary

symbol of the soul's journey to the spirit world.

In

the knowledge that the Mandaeans themselves once exposed their dead to carrion

birds (Drower, 1937, 184-5, 200), could the pigeon or dove have replaced more

unsightly birds such as the vulture and raven as symbols of the soul's flight

into the next world?

Continuing the account, we read next that:

The worshippers without, on hearing these words, 'rise and prostrate themselves upon the ground towards the North Star, on which they have silently been gazing.' 'The Ganzivro, who has made a complete renunciation of the world, and is regarded as one dead and in the realms of the blessed.' after the celebration of a kind of communion in which small cakes, sprinkled with the blood of the second pigeon are partaken of, recites a further service, 'ever directing his prayers towards the North Star, on which the gaze of the worshippers outside continues fixed throughout the whole of the ceremonial observances.'

The

Ganzivro, in his role as head of the sect, has apparently "made a complete

renunciation of the world, and is regarded as one dead and in the realms of the

blessed". This implies that through some form of initiation or rite of passage

he has renounced his earthly status in order to communicate more directly with

the Supreme Being, whose visible symbol is the Pole Star.

Can

we imagine the priests or shamans at places like Göbekli Tepe or Çayönü

undergoing similar rites of passage in order to gain access to the spirit intelligences

of the sky-world? Interestingly, in a hark back to their former use of excarnation,

the Mandaeans believe that if the shadow of a vulture or black crow passes over

a newly-deceased body the soul has gained its release (Drower, 1937, 200). In

this manner, there seems to be a connection between the departure of the soul

and the presence of the bird, almost as if the vulture or crow triggers the release

of the soul. Since raptor birds (almost certainly vultures) feature prominently

in the carved art at Göbekli Tepe, Nevali Çori and Çatal Höyük,(Peters

& Schmidt, 2004) it perhaps shows their functional role as places of life,

death and rebirth in a material as well as a metaphysical sense.

All

this begins to make it certain that the Mishkna of the Mandaeans served a function

similar to that of early Neolithic cult buildings and shrines in southeast Anatolia,

and arguably even further afield. What is more, the Mandaeans' told Mrs E. S.

Drower (1879-1972), a British anthropologist who spent a considerable time with

members of the sect in southern Iraq, that the "construction, proportions,

materials, and shape" of the Mishkna "are prescribed by written and

oral tradition, and Mandaeans assure me that this is extremely ancient-'from (the

age of) Adam'" (Drower, 1937, 124).

With a proposed line of descent from Göbekli Tepe to the Mandaeans via Tell Idris, Harran and the original Sabaean star-worshippers, it is very possible that at least some of the traditions concerning the origins and use of the mishkna cult hut stem from the Neolithic age.

Aligned

to What Star?

So

were the stone enclosures at Göbekli Tepe, like the Mishkna of the Mandaeans,

directed towards the Pole Star in its role as entrance to the sky-world? The answer

is almost certainly no, for during the epoch of their construction, c. 9500-8000

BC, no bright star marked the position of the celestial pole. There was simply

a black void where the Pole Star should have been, around which various circumpolar

and near circumpolar stars were seen to revolve in an unerring fashion. So if

not the Pole Star, can we go on to identity any other potential stellar targets

in the northern night sky?

An

examination by engineer Rodney Hale of the north-northwest alignment of the twin

central pillars in three of the sanctuaries at Göbekli Tepe (Enclosures C,

D & E) determined that at the proposed time of their construction, c. 9400-8980

BC, they targeted the setting of Deneb, the brightest star in Cygnus, the celestial

bird (Collins 2013, Collins & Hale, 2013 Collins & 2014). Moreover, a

similar survey of the north-northwest alignment of all three cult buildings at

Çayönü showed that they too are aligned to the setting of Deneb,

c. 8780-7930 BC, (Collins, 2014), dates that correspond very well with recent

revisions of radiocarbon evidence obtained in association with excavations at

the site.7

So

why the apparent interest in this particular star?

The

answer seems to lie in the fact that Deneb had been Pole Star, c. 16,500-14,500

BC, its place being afterwards taken by the star delta Cygni, a role it held through

until c. 13,000 BC. Thereafter, due to the effects of precession (the slow wobble

of the earth across a cycle of approximately 26,000 years), the celestial pole

drifted away from Cygnus and into the neighbouring constellation of Lyra. Here

it synchronized with the bright star Vega, which then acted as Pole Star through

until around c. 11,000 BC. The celestial pole then departed Lyra, entering the

constellation of Hercules. Yet here it failed to synchronize with any bright star.

So

in the age of Göbekli Tepe there was no Pole Star marking the celestial pole.

In its absence, can we imagine the astronomer priests of the early Neolithic age

turning their attentions, and their monuments, towards a previous Pole Star in

the form of Deneb.

Let's look at the evidence.

Precession

of the Pole Star

When

the stars of Cygnus synchronized with the position of the celestial pole, c. 16,500-13,000

BC, there were two ways of entering the sky-world. You could either ascend an

imagined axis mundi, or "axis of the earth", seen to connect the physical

world with the Pole Star, or you could travel along the Milky Way, accessed via

the local horizon at certain times of the year. Universally the Milky Way has

been seen as a road, river or path used by the souls of the dead, sometimes in

the form of birds, to reach the abode of the dead. All of these beliefs almost

certainly existed in the Upper Paleolithic age, with evidence that Cygnus was

seen as an access point to the sky-world as early as 15,000 BC ( Rappenglück,

1999; Collins, 2006).

Both

methods of reaching the sky-world led to the same point in the sky-a section of

the Milky Way where it splits into two separate branches due to the presence of

stellar dust and debris in line with the galactic plane. This rift or cleft begins

in the constellation of Cygnus and continues all the way down to the stars of

Sagittarius and Scorpio, where the ecliptic, the sun's path, crosses the Milky

Way. This powerful combination involving both the celestial pole and the Milky

Way's Dark Rift or Cygnus Rift, as it is called, would have led to Cygnus being

seen as a universal point of entry to the sky-world. Here the souls of the deceased,

often in the guise of a bird, would have been seen to enter the afterlife, while

new souls emerged from this point in the sky prior to incarnation, making the

celestial bird a place of rebirth on both a material and cosmic level.

In the absence of a Pole Star in the tenth millennium BC, we can now better understand why the Göbekli builders might have seen Deneb, as Cygnus's brightest star, as a point of access to the sky-world even after Vega relinquished its duties as Pole Star, c. 11,000 BC. It is almost certainly for this reason that the twin central pillars of three stone enclosures at Göbekli Tepe, as well as the cult buildings at Çayönü, targeted the setting of Deneb during the epoch of their construction.

A

Change in Direction

Over time the orientation of Neolithic cult buildings changed to accommodate new religious ideas that emerged following the rapid spread of subsistence agriculture across southeast Anatolia and the Levant during the ninth millennium BC. Yet the significance of the northern night sky remained strong until finally the Northern Hemisphere got its first notable Pole Star in several thousand years. This was Thuban, a relatively inconspicuous star in the constellation of Draco. It assumed pole position sometime around c. 3500-3000 BC, and kept the role until eventually it was superseded by the star Kochab in the constellation of Ursa Minor around c. 2500-2000 BC. Yet its glory was relatively short lived, and it was not until around the time of Christ that the star Polaris, also in Ursa Minor, became the undisputed Pole Star, a role it continues to play today. It was this star that the Mandaeans living on the banks of the Euphrates fixed their gaze during the quite remarkable festival witnessed by the London Standard correspondent towards the close of the nineteenth century. It is their knowledge, carefully guarded since the age of Adam, that we can now use to help bring alive the mysterious activities that unquestionably went on at places like Göbekli Tepe and Çayönü as much as 11,000 years ago.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Rodney Hale and Catherine Hale for their help in producing this article.

Notes

and References

1.

Hale, Rodney, Letter to the Editor of New Scientist, submitted Monday, 19 August,

2013: "The suggestion that Sirius played a part in the orientation of the

Göbekli Tepe enclosures (Issue No. 2930, 17 August, p.14) seems unlikely

since the star would suffer severe dimming at the altitude at which it would have

been visible at the time. Sirius was skimming the southern horizon, and tables

of atmospheric extinction show that Sirius has a magnitude of only 4.5 at an elevation

of one degree. Would those people have put such immense effort into building a

site pointing towards a barely visible point of light?"

2. See, Lloyd

and Brice, 1951, 77-111. They report on surface finds at Harran including distinctive

ceramic ware belonging to the Halaf culture.

3. See Gündüz, 1994,

164-166, for a full account of the sources and arguments regarding the direction

of prayer of the Sabaeans and Mandaeans.

4. Green, The City of the Moon God,

pp. 211-212.

5. See Ibid., 64-67 on the arguments relating to the Mandaeans'

origin point being Harran.

6. Mackenzie, 1926, 3, cf. Relig, des Soubbas, 124.

7.

Yakar, in Steadman and McMahon, 2011, 67, summarizing Bischoff, 2006, 2007.

Bibliography

Ananthaswamy,

Anil, "World's oldest temple built to worship the dog star", New Scientist

2930, 17 August 2013,14, http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21929303.400-worlds-oldest-

temple-built-to-worship-the-dog-star.html.

Bischoff,

Damien, CANeW 14C Databases and 14C Tables: Upper Mesopotamia (SE Turkey, N Syria

and N Iraq 10,000-5000 cal BC), http://www.canew.org.

Bischoff,

Damien, CANeW Material Culture Stratigraphic Tables: Upper Mesopotamia (SE Turkey,

N Syria and N Iraq 10,000-5000 cal BC), http://www.canew.org.

Brown,

Robert, Researches into the Origin of the Primitive Constellations of the Greeks,

Phoenicians and Babylonians, Williams and Norgate, 2 vols., London, 1900, II,

177-179.

Collins, Andrew, The Cygnus Mystery, Watkins, London, 2006.

Collins,

Andrew, Göbekli Tepe: Its Cosmic Blueprint revealed, 2013, http://www.andrewcollins.com/page/articles.Gobekli.htm

Collins,

Andrew, Göbekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods, Bear & Co., Rochester, VM,

2014.

Collins, Andrew, and Rodney Hale, "Göbekli Tepe and the Rebirth

of Sirius", 2013, http://www.andrewcollins.com/page/articles/Göbekli_Sirius.htm.

Drower,

E. S., The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, Oxford University Press, London, 1937.

Green,

Tamara, The City of the Moon God, E. J. Brill, Leiden, Holland, 1992.

Gündüz,

Sinasi, The Knowledge of Life, Oxford University Press, 1994.

Lloyd, Seton,

and William Brice, "Harran", Anatolian Studies 1 (1951), 77-111.

Mackenzie,

Donald, The Migration of Symbols, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, London, 1926.

Magli,

Giulio, "Possible astronomical references in the project of the megalithic

enclosures of Göbekli Tepe", http://arxiv.org/abs/1307.8397

[physics.hist-ph].

Peters., J. and K. Schmidt, "Animals in the symbolic

world of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey: a preliminary

assessment", Anthropozoologica 39:1 (2004), pp. 179-218.

Rappenglück,

Michael A., Eine Himmelskarte aus der Eiszeit? Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main,

Germany, 1999.

Schirmer, Wulf, "Some aspects of building at the 'aceramic-neolithic'

settlement of Çayönü Tepesi", World Archaeology 21:3 (1990),

363-87.

Steadman, Sharon R., and Gregory McMahon, The Oxford Handbook of Ancient

Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE), OUP, 2011.

Yardimci, Nurettin, Mezopotamya'ya açilan

kapi Harran, Ege Yayin Yili, Istanbul, 2008.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Fig.

1. Reconstruction of a Mandaean bit manda cult hut. This one has a roof and fenced

enclosure, unlike the one described in the London Standard article from 1894.

Note the baptismal pool, and the channels linking it to running water. From E.

S. Drower, The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, 1937.

Fig.

2. Side views of a bit manda cult hut from the north and south. Note the south

entrance door. From E. S. Drower, The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, 1937.

Fig. 3. Ground plan of a bit manda cult hut, similar in size to the mishkna mentioned in the London Standard article from 1894. Note the southerly placed entrance door, and the similarity in shape and orientation to the cult buildings found at Çayönü seen in Fig. 4. Drawing from E. S. Drower, The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, 1937.

Fig. 4. Reconstructed plans of the cult buildings at Çayönü, southeast Anatolia, in 1963. From left to right we see the Terrazzo Building, Skull Building and Flagstone Building. All three possess azimuths of orientation that suggest they pointed towards the setting of Deneb in the epoch of their construction. Picture credit: Professor Wulf Schrimer/Karlsruhe University

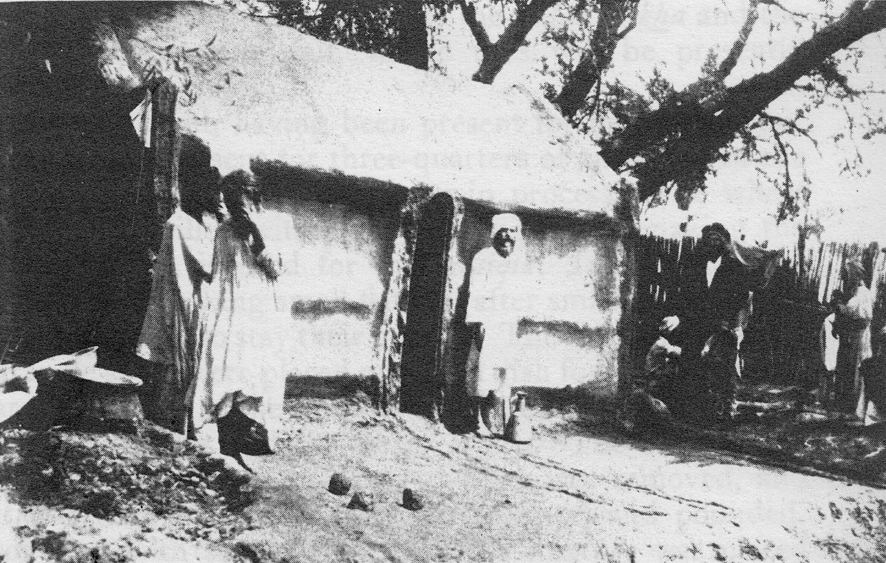

Fig. 5. Mandaean bit manda cult hut from the south. Picture from E. S. Drower, The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, 1937.

Fig.

6. Göbekli Tepe's Enclosure C with arrows indicating marks, cuts and grooves

seen on the top of pillars, suggestive of the former presence of a roof. Picture:

Andrew Collins, 2013.