K

A R A H A N T E P E

GÖBEKLI TEPE'S SISTER SITE

ANOTHER TEMPLE OF

THE STARS?

by Andrew Collins

Karahan

Tepe might be described as a sister site

to the more widely known Pre-Pottery Neolithic sanctuary of Göbekli Tepe.

Both are situated in mountainous terrain in southeast Anatolia

(the modern-day republic of Turkey), just a short distance from the ancient cities

of Sanliurfa and Harran. Both feature settings of T-shaped stone pillars, which

are anthropomorphic in nature and bear carvings either in high relief or 3D. Both

were built and then abandoned during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period. Yet whereas

Göbekli Tepe has received widespread attention, being excavated since 1995

under the auspice of the German Archaeological Institute in partnership with the

Sanliurfa Archaeological Museum, Karahan Tepe remains relatively obscure.

Professor

Bahattin Çelik of the Department of Archaeology, Harran University, was

the first to recognize the existence of Karahan Tepe, following an initial investigation

of the hill site in 1997. His team has conducted two surveys, the first in 2000

(Çelik, 2000), and the second in 2011 as part of the Sanliurfa City Cultural

Inventory (Çelik, 2011). The current author first visited the site in 2004

under the charge of the Mayor of Diyarbakir, and returned there again in 2014

in order to examine its possible function and orientation.

Location

Karahan Tepe lies just beyond the eastern limits of the Harran Plain within the remote Tektek Mountains (Tektek Dagliari). It is approximately 22 miles (35.5 kilometres) northeast of the ancient city of Harran, 23 miles (37 kilometres) east-southeast of Göbekli Tepe and 28.5 miles (46 kilometres) east-southeast of the city of Sanliurfa (see fig. 1). As an archaeological site it occupies the northern extent of a roughly north-northeast to south-southwest oriented tepe (Turkish for "hill"), covering an area approximately around 13.23 hectares (33 acres).

Fig.

1. Map showing Karahan Tepe and its relationship to the Harran Plain

(Pic courtesy:

Digital Globe/CNES/ Astrium, © 2014).

The

hill, a natural formation of Eocene and Miocene limestone (see fig. 2), is approximately

490 metres (0.3 of a mile) in length and 270 metres (0.17 of a mile) in width.

It rises from a height of 675 metres (2,215 feet) above sea-level in the valley

below to 705 metres (2,313 feet) at its summit.

The tepe is situated on

an active pastoral farm named Keçili, 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometres) east of

the village of Inci, a little way south of the Sanliurfa to Mardin highway. A

brisk walk of around 400 metres (a quarter of a mile) takes the visitor from the

farmhouse south-southeast to the base of the tepe.

Fig.

2. Map showing Karahan Tepe

(pic courtesy: TerraServer, © 2014).

Stone

Pillars

The

first thing the visitor notices when ascending the hill's northern slope are the

partially exposed heads of stone pillars that emerge into view from beneath a

hard deposit of soil that hides their stems (and sometimes most of their heads).

These sunken pillars climb toward the summit of the tepe for a distance of approximately

50 metres (164 feet), forming what appears to be a stone avenue. Its roughly north-northeast

to south-southwesterly orientation matches not only that of the hill, but also

that of the stones themselves. Two further pillars at the northern base of the

avenue are turned 90º and so perhaps formed an entranceway (like the U-shaped

gateway leading into the dromos feature forming part of Göbekli Tepe's Enclosure

C). At least three other stones nearby have the same alignment, complicating any

interpretation of the layout, and suggesting that the base of the avenue might

have included a built structure.

Fig.

3. T-shaped pillar in Karahan southeastern avenue.

Stick marker in inches.

What

might also be stone avenues, combined in some way with more complex features,

are visible on Karahan's eastern and southeastern slopes (no standing pillars

are visible on its western and southern slopes, which are predominantly exposed

bedrock without any substantial covering of soil).

These "avenues"

(see figs. 3, 4 & 9) start within 10-15 metres (30-50 feet) of the valley

floor, and ascend toward the top of the hill, their twin sets of pillars forming

an apparent zigzagging pattern. Other pillars either lying outside of the "avenue,"

or with a different orientation, again makes it difficult to decide on the exact

layout of these stone settings.

Fig.

4. Stones in Karahan Tepe's southeastern avenue

as viewed from the northwest.

Yet what does seem clear, however, is that all three "avenues" - the northern, eastern and southeastern, whose approximate azimuths are in the range of 15º, 115º and 140º respectively - are aligned toward the same spot; this being an exposed rock ledge or knoll immediately north of the hill's extended summit.

Northern

Knoll

The exposed

surface of this northern knoll marks the beginning of an extensive area of bedrock

covered with groupings of deeply bored cupules, or cup marks, usually 15 to 20

centimetres (6 to 8 inches) in diameter and easily as much in depth (see fig.

5). Similar cupules are found on exposed bedrock at Göbekli Tepe, close to

Enclosure E, the so-called Felsentempel ("Rock Temple"), and

also at other Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites such as Basaran Höyük (Güler,

Çelik & Güler, 2013, 295, fig. 11) and Hamzan Tepe (Çelik,

2010, 262, fig. 6), both located in the Sanliurfa province.

Fig.

5. Cupules close to Karahan Tepe's northern knoll.

Stick marker in inches.

Other,

much larger holes, ranging in diameter from between 40 to 50 centimetres (15 to

20 inches), are also present within the exposed bedrock. At least three sets are

placed together in pairs, giving them the eerie resemblance of dark eyes gazing

up at the beholder, a fact that, regardless of their true function, seems deliberate

(see fig. 6).

In addition to this, we find a large basin cut into the bedrock,

which is oval in shape and approximately 3 metres (9.85 feet) across its widest

part. It probably functioned as a water cistern, although this is simply conjecture

at this time (two similar rock-cut basins are to be seen close to cupule clusters

at Göbekli Tepe, and another three exist at Hamzan Tepe, again near groupings

of cupules, see Çelik, 2010, 262-3, Figs. 7/8).

Fig.

6. One of the twin sets of holes on exposed bedrock

close to Karahan Tepe's

northern knoll. Stick marker in inches.

Beyond

the carved bedrock immediately behind Karahan Tepe's northern knoll very little

evidence of occupation is visible. The southern and western slopes seem devoid

of any bedrock carving, other than a curved groove, around a metre across, carved

into a horizontal rock face about half way up the side of the southeastern slope

(see fig. 7). It terminates in a deliberate vertical fracture, probably the result

of a pillar being forcibly removed from the bedrock.

Fig.

7. Curve carved into the bedrock on Karahan Tepe's

southeastern slope. Stick

marker in inches.

Small Finds

Various small finds, including carved fragments of mini T-shaped stones and right-angled corner sections of what appear to be porthole stones, like those found at Göbekli Tepe, are to be seen on Karahan's eastern slopes (see fig. 8). Most likely these porthole stones formed vertical or horizontal openings into now lost enclosures. One noticed by the author in 2014 was being used on the summit of the hill, close to the northern knoll, to line a fire pit. Since this fragment of carved stone is likely to be over 10,000 years old, this seems a tragic misuse of such an important relic of the past.

Fig.

8. The author examining a larger fragment of a porthole stone

near the base

of Karahan Tepe's eastern slope.

Stone Tools

Stone tools, tool fragments and discarded flakes are to be seen everywhere at Karahan Tepe. Those observed include arrowheads (identified as mostly Byblos, Nemrik and Aswad points, see Çelik 2011, 244), scrapers (both side and end scrapers), borers, hammer stones, and sickle blades. These are fashioned mostly from a grey to brown flint (which was also the most favoured type of flint used at Göbekli Tepe), although fragments of stone tools in black flint and what appears to be white quartz have also been noted (although, oddly, these were seen only on the tepe's western face, close to the unfinished monolith - see below). No obsidian tools have been observed, although a fair quantity were found and recorded by Çelik and his team (see Çelik, 2000, 7, and Çelik, 2011, 243-5).

Site

Age

A cursory

examination of stone tools, combined with the complete lack of any pottery shards

at Karahan Tepe, makes it clear that the site was active during the Pre-Pottery

Neolithic, ca. 9500-6000 BC.

We can, however, narrow down these dates

still further with an examination of the T-shaped pillars visible today. Some

display deep vertical indentations running down the centre of their front narrow

faces, similar to the anthropomorphic T-shaped stones seen at Göbekli Tepe

and Nevali Çori, a now submerged site on the Middle Euphrates in the extreme

north of Sanliurfa province. This vertical fluting undoubtedly represents the

chest area between the dropping hems of garments worn by the stone figures.

Other

than this the stones remaining in situ have very little obvious carving on their

exposed heads. This said, at least one complete pillar, and several other fragments,

which all bear intricate carving, have been removed for safe keeping to Harran

University. Other pillars have, unfortunately, been either damaged or possibly

even destroyed during illegal diggings, which mostly take place at night.

Fig.

9. T-shaped pillar in Karahan Tepe's

southeastern stone avenue. Stick marker

in inches.

In size and appearance the T-shaped pillars at Karahan, which when fully exposed would stand around 2 metres (6.6 feet) in height, are comparable with those found in the youngest structures at Göbekli Tepe, such as Enclosure F, the Löwenpfeilergebaude ("Lion Pillar Building"), and the various cell-like rooms located in younger layers west of the four main enclosures, all of which date to Göbekli Tepe's final phase of construction, Level II, during the early Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period, ca. 8500-8000 BC (similar reduced sized T-shaped stones have been found at other Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites in southeast Anatolia, such as Sefer Tepe, Hamzan Tepe and Gusir Ho¨yuk (see, for example, Güler, Çelik and Güler, 2013 & Çelik, 2010, 258-9, Fig. 2). It thus seems likely that this was the main period of building construction at Karahan Tepe, a conclusion drawn also by Çelik (see Çelik, 2000, 7, & Çelik, 2011, 246).

Unfinished

Monolith

The

presence of a much larger, unfinished monolith still attached to the bedrock on

Karahan's western slope indicates that even larger, and thus much older, pillars

probably once stood at the site (the general rule at Göbekli is that the

bigger and more sophisticated the pillar, the older it is, with the earliest dating

back to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period, ca. 9500-8500 BC).

Karahan's unfinished

monolith (see fig. 10) is 5.5 metres (18 feet) in length, 2 metres (6.5 feet)

across its widest part (the T-shaped head), and around 80 centimetres (30 inches)

in thickness. Detached from the bedrock it would have weighed around 15 metric

tonnes (20 US tons). It is located immediately beneath a raised ridge or escarpment

that runs the entire length of the hill summit.

Fig.

10. Unfinished monolith on Karahan Tepe's western slope.

Place

of the Snake

On

two T-shaped pillars found at Karahan Tepe a carved snake is seen to slither up

its front narrow edge. On one, originally found in 1997 and now removed to Harran

University (see fig. 11), the snake looks like a human sperm, with a round, bulbous

head and wavy body (Çelik, 2000, 6, fig. 1, & Çelik, 2011, 243,

figs. 8,9 & 10), while on the other example, exposed during illegal digging

operations and first observed by Çelik and his team in 2011, only the dome-shaped

head of the creature is visible - the rest of its body remaining unexposed beneath

the ground (Çelik, 2011, 243, 247, figs. 11 & 13).

In

addition to this a fragment of a chorite bowl, found at the site and dating to

the same age as the T-shaped pillars, bears the relief of a zigzagging snake (Çelik,

2011, 246, fig. 24:7).

The prominence of serpentine art at Karahan might

suggest that the creature held a special place among the local population responsible

for the creation of its carved art. It is even possible that the zigzagging avenues

of stones found at the site are meant to signify the winding path of snakes, which

were seen to descend from the hill's northern knoll down into the valley below,

perhaps in the manner of lightning. This suggested directional flow is given credence

by the fact that any carving visible on pillars making up the eastern and southeastern

avenues is focused uphill, implying that the processional route between them was

downward into the valley below. However, the future excavation of currently unexposed

stones, and an examination of the stems of those pillars where only the heads

are now visible, might well reveal a different orientation for any carving, so

these ideas need to be treated with some caution.

Fig.

11. T-shaped pillar with snake carving found in 1997

(pic credit: Department

of Archaeology, Harran University).

Astronomical

Alignments

Since

the tepe rises to its maximum height immediately south of the aforementioned northern

knoll the natural inclination when standing there is to look north (see fig. 12).

Doing so directs the eye north-northwest past the farmhouse to a prominent hill

or tepe, as noted by Bahattin Çelik in his report of the site published

in 2000 (Çelik, 2000, 7). Located exactly 1 mile (1.6 kilometres) away

from Karahan Tepe, the left-hand edge of its summit is at 338º azimuth with

its right-hand edge at 341.25º (see fig. 13). This provides a mean azimuth

for the centre of the hill summit of 339.63º.

The strong presence

of this northerly-placed hill (which we shall refer to as Keçili North

Tepe - see below), along with the apparent importance played by Karahan's own

northern knoll, suggests that the latter might have been used as a backsight.

In

archaeoastronomy a backsight is a position, ideally a prehistoric sanctuary, from

which observations are made toward a foresight, usually a conspicuous geographical

feature over which, or behind which, a celestial body is seen either to rise or

set (see Gil and Belmonte, 2009, for a good example of a proposed prehistoric

foresight/backsight relationship between two sites on Gran Canaria).

If

so, then an observer standing on Karahan's northern knoll during the main period

of building activity, ca. 8500-8000 BC, might have been able to witness a celestial

event in connection with Keçili North Tepe. Should this have been the case,

it could well have some bearing on why the Karahan complex was built where it

was in the local landscape.

Fig.

12. Karahan Tepe's northern knoll,

toward which the stone avenues seem aligned.

Stellar

Target

Chartered engineer Rodney Hale was asked to investigate the matter. He determined that during the proposed epoch of construction at Karahan Tepe, the bright star Deneb (a Cyg) in Cygnus, the celestial bird, would have been seen to set into the summit of the flat-topped tepe as viewed from Karahan's northern knoll. The optimum period of observation was calculated by Hale to have been between ca. 8685 BC, when Deneb set into the hill summit's eastern edge at an azimuth of 341.25º, and ca. 8375 BC, when the star set into the hill summit's western edge at an azimuth of 338º. This information, based on the established rate of precession of Deneb at an extinction height of 2º, shows also that in ca. 8550 BC Deneb would have set down into the central area of the hill. These three dates-8685 BC, 8550 BC and 8375 BC-are simply estimates, and variations might easily be applied. Yet they do coincide pretty well with the main period of occupation at Karahan Tepe during the early Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period, ca. 8500-8000 BC. However, as Çelik speculates himself, it is possible that construction began here during the late Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period, ca. 9000-8500 BC (Çelik, 2011, 247), the unfinished monolith located on the west side of the hill perhaps being evidence of this fact.

Fig.

13. Alignments between Karahan Tepe and the northerly-placed hill (Keçili

North), showing the azimuth extent of its elevated summit. Notice also positions

of the three traceable stone avenues at Karahan Tepe . (Pic courtesy: Digital

Globe/CNES/ Astrium, © 2014).

Cygnus and the Milky Way

The

star Deneb features also in proposed astronomical alignments at Göbekli Tepe

(Collins, 2013 and Collins, 2014a), whereby the mean azimuths of twin central

pillars in two enclosures, C and D, target this same star's setting during their

proposed epoch of construction, ca. 9500-9000 BC (Collins, 2013a, Collins, 2014a,

and see, for instance, Schmidt and Dietrich, 2010, for the radiocarbon dating

evidence for Enclosure D). The significance of this star appears to lie in the

fact that it marks the northern opening of the Milky Way's Great Rift, known also

as the Cygnus Rift. Elsewhere the author proposes that this noticeable fork, or

division, in the Milky Way, which appears to split the Milky Way into two separate

streams, was seen as early as the Palaeolithic age as the entrance to a sky world,

a kind of cosmic womb from which souls emerged from before incarnation, and ultimately

returned to in death. Often this journey saw the soul taking on the form of a

bird, usually a swan, goose, eagle or vulture, all of which are associated not

only with the transmigration of the soul in various Eurasian cultures, but also

with myths and legends surrounding both the Cygnus constellation and the Milky

Way in its capacity as a road or river along which souls were able to reach the

afterlife (see Collins, 2006, Collins, 2014a, and Collins, 2014b).

So it

is possible that Keçili North Tepe (see fig. 14) played a key role in the

relationship between the physical world and that of the preternatural among the

Karahan population. Perhaps through its synchronization with the Cygnus star Deneb

and the opening of the Milky Way's Great Rift, the hill was considered a point

of contact with the ancestors, as well as a symbolic place of emergence of humankind.

No similar alignments toward prominent hills in the south have been detected.

However, Rodney Hale has identified another significant hill in the local landscape

located 2.5 miles (4 kilometres) due north of Karahan Tepe, which, due to its

unique bearing, should be investigated when time permits.

Fig.

14. Keçili North Tepe as viewed from Karahan Tepe.

Note the farmhouse

in the foreground.

The Bald Place

Several

interesting facts emerged during the author's visit to Karahan Tepe in June 2014.

After leaving the hill our party was invited to share the hospitality of the farmer.

This provided the ideal opportunity to ask a number of pertinent questions about

the site. For instance, the farmer related how the importance of Karahan Tepe

was not realised until Bahattin Çelik's first visit in 1997. In other words,

no one had ever noticed the carved stone pillars, or any other carved object or

worked stone tool, present on or around the hill site.

We

determined also that no folklore or legends are known to surround the site, which

is unfortunate as this might have helped us better understand the manner in which

the hill was viewed by past inhabitants of the area.

We did learn, however,

that Karahan Tepe was not the hill's true name. According to the farmer and his

herdsmen, it is known locally as Keçili (or Keçili Tepe), which,

as we have seen, is also the name of the farm (see fig. 15). The name "Karahan

Tepe" was applied to the hill by Bahattin Çelik, based on two local

place-names.

Keçili is a Turkish word meaning "goat",

which would make Keçili the "place of the goat." However, according

to the farmer, the meaning of keçili in this instance derives from the

Kurdish root keç (pronounced ketch, as in "ketchup"),

meaning "bald."

| So

Keçili as a place-name implies the "bald place," a reference,

it seems, to the fact that grass does not grow on the hill's summit, only on its

fringes, giving it the likeness of a bald man. Interestingly, when Bahattin Çelik

first visited the farm in 1997 he was told that the aforementioned northerly-placed

tepe was called "Keçili Tepe," even though when the current author

was there in 2014 the farmer informed him that this hill did not have a name.

To save any confusion, we shall continue to refer to the hill site bearing the

Pre-Pottery Neolithic sanctuary as Karahan Tepe, and the northerly-placed hill

as Keçili North Tepe. If, however, Çelik is right and the northern tepe is indeed the true root of the Keçili place-name, then surely this brings into question the interpretation of the name as meaning the "bald place," as now we are dealing not with Karahan Tepe, but with a different hill altogether. Indeed, what seems likely is that the usage here of the Kurdish root keç comes not from a word meaning "bald" (as is believed by the farmer and his herdsmen), but from another, more obvious meaning of keç in the Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji) language. This is "girl," "daughter," "maiden," occasionally "any woman", and even "queen", as in the queen found in a deck of cards (see "girl in Northern Kurdish," Glosbe, http://en.glosbe.com/en/kmr/girl). All these meanings are derived from the fact that keç is a feminine root word that can be applied in various different ways. |

Place of Emergence

If so, then it implies that Keçili North Tepe, arguably the original Keçili Tepe, was once considered female in nature. Should this prove to be right, it would make sense of the site's apparent synchronization in the ninth millennium BC with the bright star Deneb and the Milky Way's Great Rift. In their dual role as a perceived entry point to a sky world Keçili North Tepe might have functioned as a representational place of emergence of humankind, similar to the concept of the sipapu among the ancient Pueblo peoples of the American southwest.

Sipapu was the name given to the portal through which the first peoples were thought to have emerged from the underworld, envisaged in terms of the womb of the Great Mother. The sipapu was identified by the Hopi tribe with a flat-topped hill with a circular depression in its summit located in the Little Colorado Gorge, just upstream from where the Little Colorado meets the Colorado river, in the Marble Canyon area of the Grand Canyon (O'Brien, 2012, and see fig. 16).

Fig.

16. Hopi sipapu, or place of emergence of humankind

from the underworld, located

in the Little Colorado Gorge.

Symbolically and ritualistically the sipapu was represented by a small circular hole cut into the floor of the Hopi's kiva huts (see fig. 17). By entering the kiva, the Hopi initiate was able to return to the Great Mother (Leeming, 1996, 28), a process that might well be reflected in the design and layout of Pre-Pottery Neolithic cult buildings at places like Göbekli Tepe.

Fig.

17. Hopi kiva hut with sipapu arrowed. The larger hole is a fire hearth

(pic

courtesy: Mesa Verde National Park/Wiki Commons Agreement).

Soul

Holes

Circular

holes like those found in Hopi kivas are also seen at Göbekli Tepe. Large,

flat, rectangular stone slabs with porthole-like apertures are located in the

perimeter walls of Enclosures C and D. In each case the holed stones are positioned

toward the north-northwest, exactly in line with the mean azimuths of the twin

central monoliths erected in both structures (see fig. 18).

An entrant

standing between the twin monoliths in either building during the epoch of their

construction, ca. 9000 and 9400 BC respectively, would have been able to witness

the setting of Deneb and the Milky Way's Great Rift exactly in line with the stone's

circular aperture (Collins, 2014a).

The use of these so-called seelenloch,

or "soul holes," as they are often described in connection with megalithic

dolmens in Western Europe, adds still further to the idea that synchronization

with Deneb and the Milky Way's Great Rift related to cosmological beliefs regarding

the emergence of the soul prior to incarnation, and its return in death to a sky

world seen in terms of a womb belonging to some kind of progenitor of humankind.

Fig.

18. Göbekli Tepe's Enclosure D,

with the holed stone in its perimeter

wall arrowed.

Karahan's Ancient Population

Like

Göbekli Tepe, Karahan would appear to have been abandoned sometime around

8000 BC. Why this happened when it did remains unclear. However, with the emergence

of agriculture and animal husbandry right across the region sometime around 9000

BC, it is possible that religious activities began changing in accordance with

this new way of life.

It might even have been the case that the sun, as

the obvious ripener of crops, started to take on a more central role in the construction

and alignment of cult buildings at sites like Göbekli Tepe. This is perhaps

seen in the layout, orientation and carved decoration within the Lion Pillar Building

constructed at Göbekli Tepe, ca. 8500-8000 BC.

Fig.

19. Göbekli Tepe's Lion Pillar Building with its twin pillars

set into

a stepped bench at its eastern end.

Unlike the older, much grander, structures found at Göbekli Tepe, such as Enclosures B, C and D, which are all aligned north-northwest to south-southeast, due most probably to its builders' interest in the rising and/or setting of stellar objects in the polar regions, the Lion Pillar Building is aligned almost precisely east-west (see fig. 19). Rearing lions appear in carved relief on the inner faces of twin pillars positioned at the structure's eastern end (see fig. 20), the direction, of course, of the equinoctial sunrise.

Fig.

20. The lion carving on the northern twin pillar

in Göbekli Tepe's Lion

Pillar Building.

In

this instance the carved lions perhaps represent the might and influence of the

sun (in much the same way that the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet did in ancient

Egypt). Equally, these leonine creatures could well have symbolised the star group

we know today as the constellation of Leo, the celestial lion of Greek and Babylonian

astronomy (see Belmonte and García, in press). During the ninth millennium

BC the stars of Leo rose heliacally at the time of the spring equinox, exactly

in line with the easterly orientation of the Lion Pillar Building.

Indeed,

this realization could well hint at the origin of the connection between the Leo

constellation and the figure of a lion as a universal solar symbol. In other words,

it was perhaps at this time, in the wake of the Neolithic revolution in southeast

Anatolia, ca. 9000 BC (Barbier, 2010), that the celestial lion first came to express

the power of the sun in its role as the bringer of a fruitful harvest.

Other

younger structures at Göbekli Tepe seem to bear out this shift in interest

from stellar targets in the polar regions to the rising and setting of the sun.

For instance, Enclosure F is oriented west-southwest to east-northeast to within

a degree of the rising of the sun at the time of the summer solstice and the setting

of the sun at the winter solstice (see Collins, 2013c).

Clearly, some kind

of transition from a stellar, and perhaps even lunar, based cosmology to one more

associated with the sight of the sun seems to have been occurring among the megalith-building

communities of southeast Anatolia, ca. 9000-8000 BC.

Conclusions

The

focus of Karahan Tepe's three stone avenues toward the site's northern knoll,

where the exposed bedrock is covered in cupules, as well as larger twin holes

and a possible water cistern, tells us that this was most likely its principal

area of ritual activity. That this northern knoll might also have acted as a backsight

for observations of the Cygnus star Deneb and the opening of the Milky Way's Great

Rift, which at the time would have been seen to set down into Keçili North

Tepe, suggests that what was occurring here, ca. 8500-8000 BC, was related to

the proposed stellar-based cosmology established at Göbekli Tepe as early

as ca. 9500-9000 BC (that is, before the transition to an agricultural-based economy

among the peoples of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic in southwest Asia).

If correct,

then it implies that whilst Göbekli Tepe was beginning to adopt more solar-based

religious concepts, the Karahan population upheld much older, stellar based beliefs

and practices, which may have originated among the hunter-gathering societies

of the Upper Paleolithic age (Collins, 2014a).

If so, then could the Karahan

population have been a breakaway group - one that came about as the result of

a schism at cult sanctuaries such as Göbekli Tepe regarding the nature of

the religious beliefs and observances being introduced in the wake of the Neolithic

revolution? Did the Karahan population continue to venerate key stellar objects

long after the Göbekli builders had begun to align their monuments toward

the rising and setting of the sun at important moments in the solar calendar,

most obviously the equinoxes and solstices? Did some of the stellar-based ideas

adopted at Karahan Tepe persist among the Neolithic communities of the Harran

plain, only to be inherited in much later times by those responsible for the foundation

of the city of Harran, as well as the ancient cult center of Sogmatar, located

just to the south of Karahan Tepe?

The inhabitants of Harran and Sogmatar,

known to history as the Sabaeans, along with their own descendents, such as the

Mandaeans of Iran and Iraq, and the Ismaili sect of Ikhwân al-Safâ'

("Brethren of Purity"), are all recorded as having venerated the north

as the direction of the Primal Cause (see Collins, 2006 & Collins 2013b).

Very possibly these religious beliefs stemmed from much earlier Neolithic beliefs

and practices involving the importance of key stellar objects located in the northern

polar region.

All these ideas must remain speculation at this time, although

trying to understand Karahan Tepe in terms of a sacred site where stellar observations

could be performed seems a viable proposition. Indeed, it is possible that what

was taking place here, ca. 8500-8000 BC, could tell us much about what was occurring

23 miles (37 kilometres) away at the much larger, and far more famous, site of

Göbekli Tepe, where the revolution in all things Neolithic really began.

Bibliography

Barbier,

Edward B. Scarcity and Frontiers: How Economies Have Developed Through Natural

Resource Exploitation. Cambridge, Cambs.: Cambridge University Press, 23 December,

2010.

Belmonte, Juan Antonio, Cosmology Across Cultures. A.S.P. Conf.

Ser. 409, 2009.

---. and A. César González García. "Astronomy,

landscape and power in Eastern Anatolia." In Rappenglueck, 2015 (in press).

Çelik,

Bahattin. "A New Early-Neolithic Settlement: Karahan Tepe." Neo-Lithics

2-3/00 (2000b): 6-8. Available at: http://www.exoriente.org/docs/00019.pdf

---. "Hamzan Tepe in the light of new finds." Documenta Praehistorica

37 (2010), 257-68.

---. "Karahan Tepe: a new cultural centre in the Urfa

area in Turkey." Documenta Praehistorica 38 (2011), 241-53. Available

at: http://arheologija.ff.uni-lj.si/documenta/pdf38/38_19.pdf

Collins,

Andrew. The Cygnus Mystery. London: Watkins Books, 2006.

---. "Göbekli

Tepe: Its Cosmic Blueprint Revealed (2013a)." http://www.andrewcollins.com/page/articles/Gobekli.htm.

---.

"Göbekli Tepe and the Worship of the Stars: A Question of Orientation

(2013b)," http://www.academia.edu/4315208/Collins_Gobekli_Tepe_and_the_Worship_of_the_Stars.

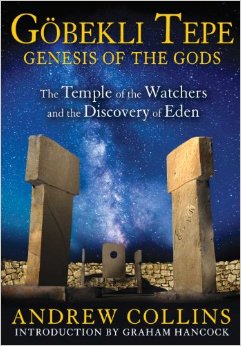

---.

Göbekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods. Rochester, VM: Bear & Co, 2014a.

---.

"Of Stars and Giants: Guardians of the Starry Wisdom (2014b)" In Little,

209-226.

Collins, Andrew, and Rodney Hale. "Göbekli Tepe and the

Rebirth of Sirius (2013c)." http://www.academia.edu/5349935/GOBEKLI_TEPE_AND_THE_RISING_OF_SIRIUS.

Gil,

Jose´ Carlos, and Juan Antonio Belmonte, "Gran Canaria Revisited."

In Belmonte, 2009, 331-7.

Güler,

Gül, Bahattin Çelik and Mustafa Güler. "New Pre-Pottery

Neolithic sites and cult centres in the Urfa Region." Documenta Praehistorica

40 (2013), 291-303.

Leeming, David Adams. Goddess: Myths of the Feminine

Divine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Little, Greg, Path of

Souls: The Native American Dream Journey. Memphis, TN: ATA-Archetype Books,

2014.

O'Brien, Christopher, "May 2012: Expedition to Sipapu 'The Place

of Emergence' Part One," 21 July, 2012, Our Strange Planet, http://www.ourstrangeplanet.com/5-14-2012-expedition-to-sipapu-the-place-of-emergence/.

Rappenglück,

M., ed. Astronomy and Power: Proceeedings of the SEAC2010 Conference, 2015 (in

press).

Schmidt, Klaus, and Oliver Dietrich. "A Radiocarbon Date from

the Wall Plaster of Enclosure D of Göbekli Tepe." Neo-Lithics

2:10 (2010): 82-83.

The author would like to extend his gratitude to Rodney Hale, Catherine Hale, Juan Antonio Belmonte, Greg Little, Richard Ward, Hugh Newman, as well as all those who participated in the Origins of Civilization tour in May-June 2014, for the part they played in the creation of this article.

A

few additional things on Karahan Tepe:

"One Week in Kurdistan" - Andrew's first visit to Karahan Tepe and Göbekli Tepe in June 2004:

http://www.andrewcollins.com/page/articles/kurdistan.htm

A

video featuring Andrew Collins and Hugh Newman's visit to Karahan Tepe as part

of the Origins of Civilization tour in June 2014:

http://youtu.be/JGaGH2WY5Wc

Hugh

Newman's video report on Karahan Tepe's unfinished monolith

http://youtu.be/CXoCRP3isAM

Short

article on Karahan's unfinished monolith by Hugh Newman

http://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe-opinion-guest-authors/forgotten-stones-karahan-tepe-turkey-001917#!bCFVi5

AVAILABLE

NOW |

![]()