![]()

Report by Andrew Collins author of From the Ashes of Angels (1996), The Cygnus Mystery (2006) and Beneath the Pyramids (2009)

On

a hilly ridge called Göbekli Tepe in the Taurus Mountains of southeast Turkey,

near the ancient city of Sanliurfa, archaeologists have uncovered the oldest stone

temple complex in the world. Constructed most probably during the second half

of the tenth millennium BC, some 7,000 years before Stonehenge and the Great Pyramid,

the site consists of a series of rings of enormous T-shaped pillars, many bearing

carved reliefs of Ice Age animals, strange glyphs and geometric forms.

But what exactly were these stone enclosures used for, and were they aligned to the stars? Already there have been claims they reflect an interest in the constellation of Taurus, the Pleiades and Orion, but what is the real truth? What is the true key to Göbekli Tepe? What exactly was its function, and did its greater purpose involve a synchronization with the celestial heavens?

In the knowledge that megalithic monuments worldwide have been found to possess alignments towards celestial bodies, it is reasonable to suggest that something similar might have been going on at Göbekli Tepe, with the most obvious candidates for orientation being the various sets of twin pillars. These could well have acted as astronomical markers of some kind, especially in the knowledge that in the past a clear view of the local horizon in all directions would have been available from the position of the various enclosures, which grace the summit of a mountain ridge visible for miles around.

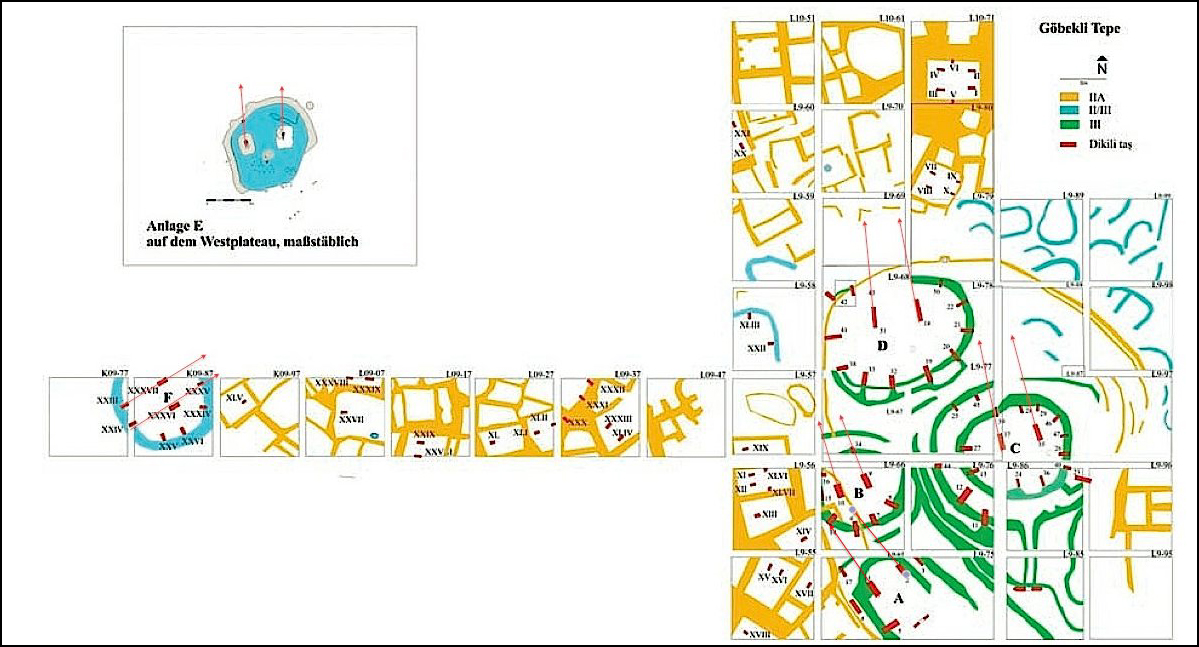

Plan

of Göbekli Tepe created by the German Archaeological Institute. Enclosures

A, B, C, D and F are in context, with Enclosure E shown as a satellite due to

the fact that it lies outside of the main group of structures. However, please

note that the orientation of the various enclosures shown here differs very slightly

from those on original survey plans (Pic credit: German Archaeological Institute).

Finding

the Orientation

Identifying

the potential stellar targets of the twin pillars in the various enclosures is

hugely important, for it could reveal two very significant pieces of information.

Firstly, it can allow us to better understand the cosmological beliefs and practices

of the Göbekli builders and, more importantly, it might well offer potential

construction dates for the various enclosures due to the effects of precession

(again, below).

Establishing

the orientations of the enclosures' central pillars was put to chartered engineer

Rodney Hale, who for the past fifteen years has made a detailed study of stellar

alignments at prehistoric and sacred sites around the world. He examined published

and unpublished survey plans of the monuments at Göbekli Tepe and determined

that the central pillars in Enclosures B, C, D and E (the "Felsentempel",

or "rock temple", located to the west of the main group) are all aligned

just west of north, and, equally, just east of south, in the following manner:

Enclosure B 337°/157°

Enclosure C 345°/165°

Enclosure D 353°/173°

Enclosure E 350°/170°

The twin pillars marking the entrance to an apse-like feature at the northern end of Enclosure A were turned much further west. Indeed, they were orientated 312°/132°, just three degrees off northwest-southeast.

The

Effects of Precession

The slight differences in the mean azimuths of the central pillars in Enclosures B, C, D and E is telling, for it could suggest that each set might have targeting the same stellar object as it very gradually shifted its position against the local horizon due to the effects of precession. This is the slow wobble of the earth, which results in a slow drift in the stellar background across a period of around 26,000 years. Since stars rise in the east and set in the west, this tells us that the enclosures could have targeted a celestial object that set each night on the north-northwestern horizon. Equally, the enclosures could have been aligned towards a potential astronomical target on the southern horizon.

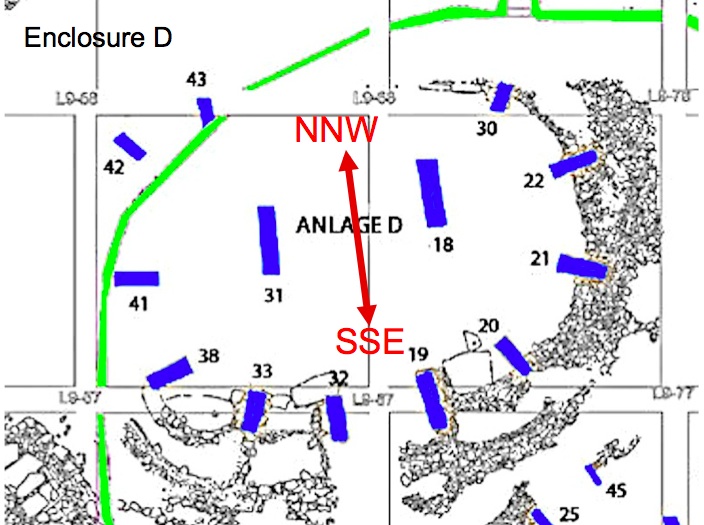

|  |

Example of the NNW-SSE alignment of the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe. Here we see the central pillars of Enclosure D, and their mean azimuth bearing, which is slightly west of north, or east of south. Pic credits: Left, Andrew Collins; right, German Archaeological Institute.

As

viewed from the northern hemisphere, the southern celestial pole is never visible.

It remains beneath the horizon, causing a plethora of stars to rise in the east,

arch across the southern sky and then set in the west. In the tenth and ninth

millenniums BC, the effects of precession were causing stars on the southern horizon

to rise and set ever further away from due south. This raises the question of

whether or not the central pillars in the main enclosures at Göbekli

Tepe targeted a

stellar object on the south-southeastern horizon that was gradually rising ever

more east of south.

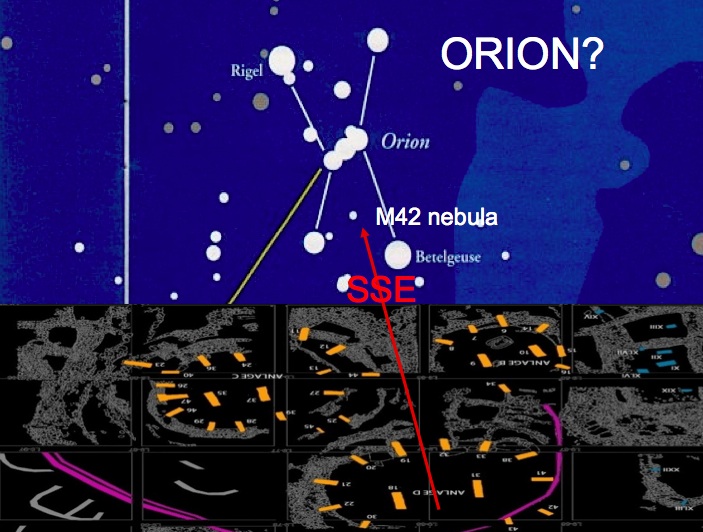

| An Orion Correlation? Among the southern star groups and constellations looked at by Hale were the Hyades, Taurus, the Pleiades and Orion (more specifically its three "belt" stars), all of which have been put forward as matching the orientations of the twin pillars in the various enclosures at Göbekli Tepe during the epoch of their construction, c. 10,000- 9000 BC (see, for instance, Dr Robert Schoch's latest book Forgotten Civilization, 2012). Out of these, just one potential candidate emerged as perhaps playing some role at Göbekli Tepe, and this was Orion, the celestial hunter. |

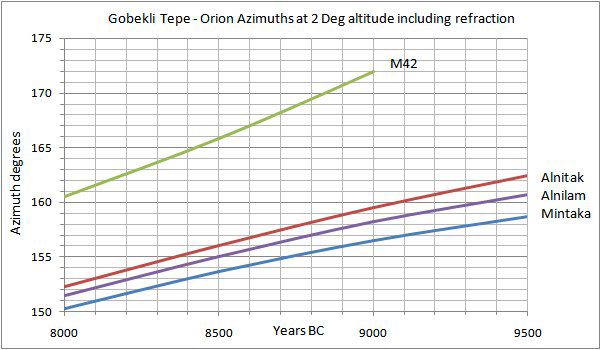

Rodney Hale charted the risings of all Orion's principal stars between the dates 9500 BC and 8000 BC, and then matched this information against the window of opportunity created by the orientations of the central pillars in the various enclosures at Göbekli Tepe. This brought out a massive problem. Although there were potential alignments between one or other of these stars and Enclosures B and E, the mean azimuths of the central pillars in Enclosures C and D did not target any of Orion's stars during the epoch in question, as you can below:

|

|

| Top, chart created by engineer Rodney Hale showing the rising azimuths of the Belt stars of Orion and Messier 42 from 9500 BC through till 8000 BC, the time frame of construction at Göbekli Tepe. Then, below, you can see correspondences between the mean azimuths of the various sets of twin pillars in the different enclosures, against the rising date reflected for the star or stellar object in question. |

The

pillars of Enclosure E would have targeted the rising of the fuzzy object known

as Messier 42 in the sword of Orion in 8840 BC, but the suggested date of 8430

BC for its synchronization with the central pillars of Enclosure C makes no sense

whatsoever. With respect to the risings of Orion's three belt stars, although

one or other of them synchronize with the twin pillars in Enclosure B (Al Nitak

in 8630 BC, Alnilam in 8800 BC and Mintaka in 9100 BC), none of the stars align

in any way with the remainder of Göbekli Tepe's main enclosures. Orion's

other key stars (Betelgeuse, Bellatrix, Saiph and Rigel) fared even worse than

the belt stars, making it clear that Orion is extremely unlikely to have

been the target of the various sets of twin pillars at Göbekli Tepe.

North

or South?

In fact, there is a fundamental problem in even assuming

that the enclosures face south, for even though the central monoliths are all

turned in this direction, there is no reason to assume they are observing the

southern sky-line. More likely is that they face the entrant approaching from

the south, in the same way that statues in churches face the entrant approaching

the high altar. Church altars are placed in the east, since this is the direction

of heaven in Christian tradition. Just because Jesus or the Virgin Mary face in

the opposite direction doesn't mean they are gazing out towards the western sky-line.

In

Göbekli Tepe's case, if its enclosures did have a high altar, it would have

been in the north, the direction of darkness, where the sun never rises. It is,

however, the direction of the celestial pole, the turned point of the heavens.

Northerly orientations of early Neolithic cult buildings have been determined

in Anatolia at Çayönü, Nevali Çori, and Hallan Cemi. Thus

it seems likely that Göbekli Tepe's enclosures are oriented towards the north,

not the south. Indeed, the T-shaped termination of Enclosure D's eastern central

pillar is tilted downwards in order to greet the entrant, like some kind of god-king

receiving his subjects.

Assuming that Göbekli Tepe's central pillars face south without taking into account the significance the north plays in Anatolia's early Neolithic tradition, and even later among the Sabian inhabitants of Harran, the city down on the Harran plain, overlooked even today by Göbekli Tepe, would be very foolish indeed. With this in mind, Hale now turned his attentions to the northern sky to identify any potential stellar targets here.

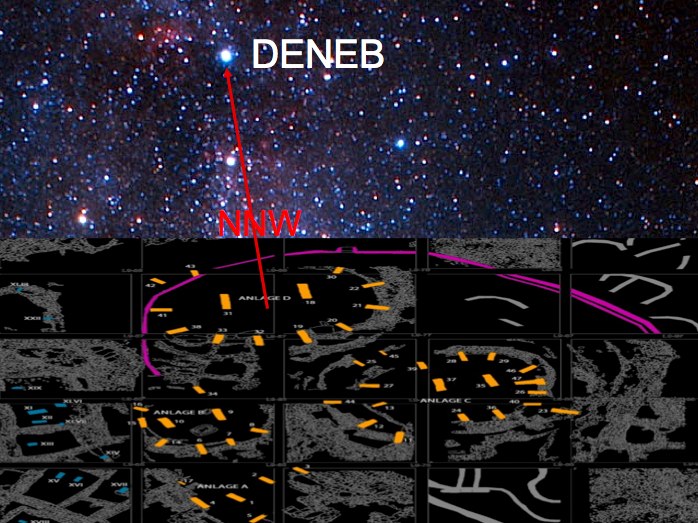

Target

Revealed

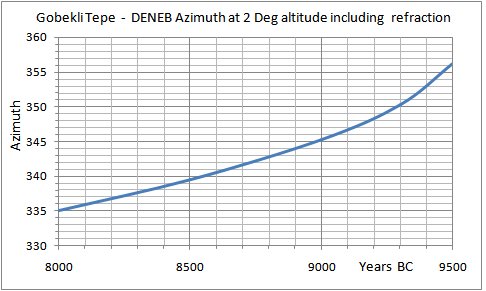

Just one star emerged as a potential candidate, and this was Deneb, the brightest star in Cygnus, the celestial bird or swan, also known as the Northern Cross. Before 9500 BC Deneb was circumpolar, in that it never set, although after this time it began extinguishing each night on the north-northwestern horizon. As the centuries went by, the effects of precession shifted the star's setting position further and further west of north in a manner that not only made sense of the alignments of the various sets of twin pillars at Göbekli Tepe, but also provided realistic construction dates for the enclosures in question, as we can see here:

Enclosure

D @ 353° = 9400 BC(1)

Enclosure E @ 350° = 9290 BC

Enclosure C @

345° = 8980 BC

Enclosure B @ 337° = 8245 BC

These dates should not been seen as absolute, since we do not know what level of accuracy the Göbekli builders employed in their building construction. Even an error of just one degree could alter the proposed alignment date by as much as one hundred years. Having said this, the suggested construction dates of the various pairs of central pillars offered by the proposed Deneb alignment correlate well with available radiocarbon dating evidence relating to the different enclosures.

| ||

Left,

chart showing the setting azimuths of Deneb during the epoch in question. Right,

reconstruction of the view from Göbekli Tepe towards the stars of Cygnus

(for visual purposes only, not to scale). |

The

Deneb Alignments

For

instance, loam taken from wall plaster found in Göbekli Tepe's Enclosure

D has provided a radiocarbon age of 9745-9314 BC,(2) which corresponds pretty

well with a suggested date of c. 9400 BC offered by the proposed Deneb alignment

of its twin pillars. Strangely, bone samples taken from Enclosure B have provided

a radiocarbon age of 8306-8236 BC,(3) which also coincides with the implied construction

date of c. 8245 BC suggested by the Deneb alignment. However, according to radiocarbon

specialist Oliver Dietrich of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), these

dates for Enclosure A could refer to late burials made shortly before the structure

was abandoned.(4) Other radiocarbon dates have been obtained from organic materials

found in the fill used to cover the major enclosures, and these range from the

late tenth through to the late ninth millennium BC, the time of the site's final

abandonment.(5)

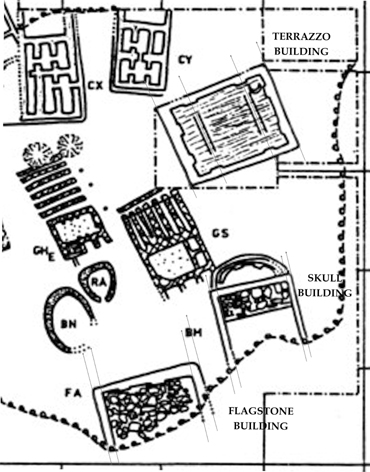

So we can see that the dating evidence emerging from Göbekli

Tepe is in no way contradictory to the possibility that the central pillars in

its main enclosures were erected and aligned to reflect the precessional shift

of an astronomical target such as the star Deneb in Cygnus. There is evidence

also that cult buildings at other Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites in southeast Turkey

might also have been aligned to the star Deneb. For instance, the Flagstone Building,

Skull Building and Terrazzo Building at Çayönü, a Pre-Pottery

Neolithic site located northwest of the city of Diyarbakir, are all aligned north-northwest

with entrances toward the south. Rodney Hale checked their orientations, based

on available plans, and established that they reflected alignments towards the

setting of Deneb during the eighth and ninth millenniums BC.(6)

Section of the 1987 plan of Çayönü, showing the basic alignments of the three cult buildings. | Structure

- Azimuth - Deneb setting date These

dates accord with recent revisions of existing radiocarbon dates obtained at Çayönü

during the 1960s, which almost all fall within the late eighth and ninth millenniums

BC.(7) Having said this, we simply have no real idea of what degree of accuracy

the Çayönü builders might have been aligning their monuments

towards the celestial horizon. so these dates should be treated with some caution. On the subject of which enclosure uncovered so far at Göbekli Tepe is the oldest, lead archaeologist Professor Klaus Schmidt of the DAI is in no doubt-it is Enclosure C. If so, then this would make it older than the 9745-9314 BC radiocarbon date range offered for Enclosure D. His reasoning behind this conclusion is that Enclosure D's outer perimeter wall abuts that of Enclosure C.(8) |

Yet

a counter argument against Enclosure C being older than Enclosure D is easily

made. If the former was constructed after the latter, then it is possible that

Enclosure D's pre-existing boundary wall was partially dismantled and reconstructed

in order to allow the completion of C's own boundary wall.

Overhead shot of Enclosure C (left) and Enclosure D (right), showing their abutting outer walls, which archaeologist Professor Klaus Schmidt says provides evidence that C is older than D. However, it might easily be argued that part of D's perimeter wall was reconstructed to accommodate the building of C's slightly later outer wall. Moreover, from the picture it seems apparent that the two walls abut each other without actually overlapping. Schmidt's full argument will, hopefully, be published in due course. Pic credit: German Archaeological Institute. |

If

Enclosure D was built first, then there is every possibility that its central

pillars do target Deneb as it extinguishes on the north-northwestern horizon,

and that the stellar alignments proposed for the other monuments are valid. Based

on these dates, Enclosure E. where only the slots in the pedestals remain to show

where the twin pillars were once placed, was constructed some 110 years after

Enclosure D, around c. 9290 BC. Its central pillars targeted Deneb, although by

this time the star was setting three degrees further west than it was when Enclosure

D was built. According to Hale's calculations, Enclosure C's central pillars reflect

a construction date of c. 8980 BC, suggesting that they were turned even further

west in order to target the setting of Deneb at this time.

Having said

this, the rectangular slots cut out of the raised pedestals sculpted from the

bedrock in order to support Enclosure C's twin monoliths are in actuality twisted

slightly further north than the pillars themselves. They are askew only by a degree

or so, although the difference between the stones and their slots is noticeable.

This might indicate that the pillars are aligned to Deneb at a date slightly after

the construction of the slots, which could reflect the position of the star at

an earlier date. If so, it implies that the enclosure is in fact older than the

8980 BC date suggested by the proposed alignment of its twin pillars towards Deneb,

perhaps by as much as 100 years. It is even possible that the monoliths were repositioned

when it was realised that they no longer synched with the setting of Deneb determined

when the pillars were first erected. So were they shifted slightly further west

of north in order to reflect the star's new setting position on local horizon

sometime around 8980 BC? It is very possible.

Other structures

Other

structures at Göbekli Tepe were built perhaps with different considerations

in mind. Enclosure B's central pillars are unlikely to have targeted Deneb during

the epoch in question. The twin pillars marking the entrance to the apse in Enclosure

A were orientated almost exactly northwest to southeast, while those in Enclosure

F (a smaller, much later structure west of the main group) are aligned east-northeast

or west-southwest, very close to the angle at which the sun rises on the summer

solstice and sets on the winter solstice.

On top of this there are a number

of other cell-like structures at Göbekli Tepe, and these are orientated all

over the place. They are much younger in age, being built in the ninth millennium

BC, and so quite possibly the motivations behind their construction had changed

by this time. No longer, it seems, was it necessary to adhere rigidly to the ways

of the ancients.

Sighting

Stone Discovery

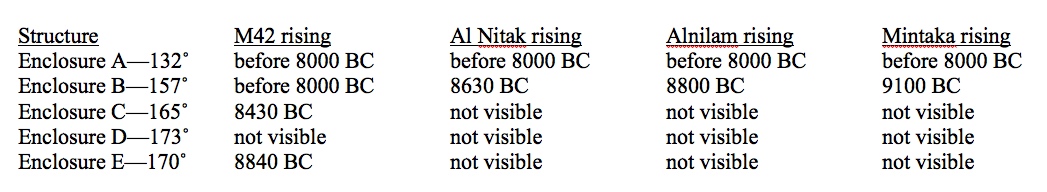

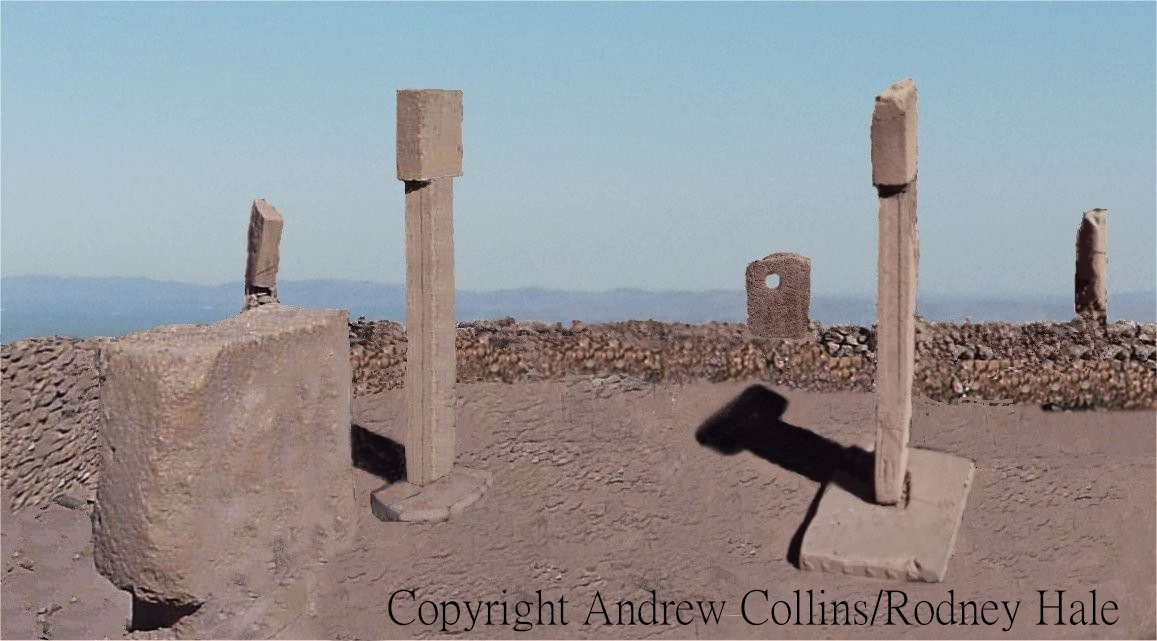

Further

evidence of Göbekli Tepe's proposed astronomical alignments comes from Enclosure

D. A small stone pillar standing around five feet (1.5 m) in height has been found

in its north-northwestern perimeter wall, exactly behind and in line with its

central pillars. The stone is rectangular in shape and, unlike the rings of radially

oriented pillars in the various enclosures, has one of its wider faces turned

towards the centre of the structure.

The significant point about this stone

is that it has a large hole some seven to eight inches (18-20 cm) in diameter,

located about four (1.2 m) feet off the ground, making it a perfect sighting post.

Covering the stone are a series of curved lines, which flow in pairs and come

together just beneath the hole and then trail off, at a slanted angle, towards

the stone's right-hand corner. Very likely they are a naive representation of

the human torso with legs coming together and bent towards the right-hand edge

of the stone. If so, then this would make the hole synchronous with the vulva,

or human birth canal.

|  |

Left, Rodney Hale's reconstruction of Enclosure D's original appearance, complete with sighting stone visible. The stone wall would have been higher, although how much is not known. Right, the holed sighting stone, which perhaps represents an abstract female torso and legs, the hole signifying her vulva. Pic credits: left, Andrew Collins/Rodney Hale; right, Andrew Collins.

If the enclosure's twin pillars were indeed orientated towards Deneb during the epoch in question, then a person, a shman or priest perhaps, would have been able to look through the stone's sighting hole in order to see Deneb setting on the north-northwestern horizon.

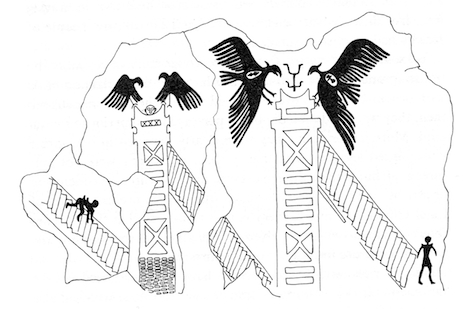

The vulture stone (Pillar 43) at Göbekli Tepe. Note the scorpion in the register below the bend winged vulture (Pic credit: German Archaeological Institute). | Göbekli's

Vulture Stone Confirming the Göbekli builders' apparent interest in Cygnus is Pillar 43. Located in the north-northwestern section of Enclosure D, it stands just a few yards away from the holed stone. On the stone's western face are two vultures, one of which is a juvenile. Also visible is a scorpion and two wader birds-flamingos perhaps-and between them and the head of the adult vulture in the upper register is a line of small squares, abutting which on either side are a series of V-shapes, possibly signifying the flow of water. There are other strange features depicted on this stone, including three rectangular forms in a line with loops that make them resemble handbags, with a bird, quadruped, another bird of some sort, and a creature of indeterminate species close by. Exactly what this scene represents is currently unknown. |

Yet

this is not why Pillar 43 has been singled out as important. It is the vulture

positioned at the end of the line of small squares that draws the eye. It stands

erect, with its wings articulated in a manner resembling human arms. It also has

slightly bent knees (or it is pregnant) and bizarre flat feet, in the shape of

oversized clowns' shoes, indicating that this is very likely a shaman in the guise

of a vulture, or a spirit bird with anthropomorphic attributes.

Similar

vultures with articulated legs are depicted on the walls of shrines at Çatal

Höyük, the Neolithic city in southern-central Turkey, which dates to

c. 7000-5600 BC, and these too are interpreted either as anthropomorphs, or shamans

adorned in the manner of vultures.(9)

| Head

Like A Ball Just above the vulture's right wing is a carved circle, like a ball, or sun-disk. Klaus Schmidt interprets this "ball" as a human head, and this is almost certainly what it is, for on the back of another vulture lower down the register is a headless, or soulless, figure, just like the examples found in association with the vultures and excarnation towers at Çatal Höyük. And we can be sure that the "ball" does indeed represent a human head as similar balls are seen in the prehistoric rock art of the region, where their context also makes it clear they represent human souls.(10) As Anatolian prehistoric rock art expert Muvaffak Uyanik makes clear: |

The wall panel showing excarnation towers and vultures at Çatal Höyük Pic credit: Andrew Collins, after James Mellaart. |

"In the Mesolithic age (i.e. in the epoch of the Göbekli builders), it was realized that man had a soul, apart from his body and, as it was accepted that the soul inhabited the head, only the skull of the human body was buried. We also know that the human soul was symbolized as a circle and that this symbol was later used, in a traditional manner, on tomb-stones without inscriptions."(11)

So the headless figure represents not only the human skeleton, but also a dead man whose soul has departed in the form of a ball-like head that is now under the charge of the vulture, which is itself arguably a shaman in the guise of a vulture. Clearly, Göbekli Tepe's Pillar 43-or the Vulture Stone as we shall call it-conveys in symbolic form the release of the soul into the care of the vulture in its role as psychopomp, or soul carrier, on its journey into the afterlife (Schmidt's suggestion(12) that the vulture is playing with a human head as part of some macabre game is simply inadequate to explain what is going on here).

Vulture

Wings

Evidence

of vulture-related shamanism has been found at other sites across the region.

Aside from those displayed both in relief and as portable art at both Göbekli

Tepe and Nevali Çori, a prime example of the Neolithic cult of the vulture

came to light in the 1950s. At an open-air settlement called Zawi Chemi Shanidar,

overlooking the Greater Zab river in the Zagros Mountains of northern Iraq, American

archaeologists Ralph and Rose Solecki discovered the wings of seventeen large

predatory birds, along with the skulls of at least fifteen goats and wild sheep.

Among

the species of bird represented by the bones, many of them still articulated,

were the Gyptaeus barbatus (bearded vulture) and Gyps fulvus (griffon

vulture), as well various species of eagle. They were found positioned by the

wall of a stone structure, which probably served a cultic purpose.(13) The excavators

were in no doubt that the wings had been severed from the birds at the point of

death, and worn as part of a ritualistic costume.(14) In other words, shamans

utilized these wings as "ritual paraphernalia"(15) in order to adopt

the guise of the vulture, in its role as a primary symbol of the cult of the dead.

The

wings were radiocarbon dated to c. 8870 BC (+/- 300 years),(16) although modern

forms of recalibration (due to recent reassessments of the amount of Carbon-14

present in organic matter during former ages) means they probably date to the

Younger Dryas period,(17) i.e. shortly before the construction of the large enclosures

at Göbekli Tepe, which as the crow flies is about 280 miles (450 km) west

of Zawi Shanidar.

Star

Map in Stone

If

Göbekli Tepe's Vulture Stone does show a human soul being accompanied into

the afterlife by a psychopomp in the likeness of a vulture, then there has to

be a chance that its rich imagery contains themes of a celestial nature. Scholars

working in the field of archaeoastronomy have been quick to point out that the

scorpion shown at the base of the shaft could signify the constellation of Scorpio.(18)

Certainly, in Babylonian astronomical texts, such as those found on the so-called

Mul-Apin tablets, the stars of Scorpio are identified with a constellation named

Scorpion (MULGIR.TAB).(19)

In the cosmological art of the Maya in Central

America a scorpion is often shown at the base of the World Tree, a symbol interpreted

by some scholars as the Milky Way standing erect on the horizon. This has led

to the scorpion being identified with the constellation of Scorpio,(20) which

is located where the ecliptic, the sun's path, crosses the Milky Way at the exact

point that the Dark Rift ends. This is the dark area of stellar dust and debris

that splits the Milky Way into two separate streams in the vicinity of the stars

of Cygnus. Universally, this has been seen as an entrance to a sky-world reached

via the arch-like opening created by the Milky Way's Dark Rift. Thus it is conceivable

that there once existed a universal identification of the stars of Scorpio with

the scorpion that went back to the Paleolithic age, the reason for its presence

on Göbekli Tepe's Vulture Stone.

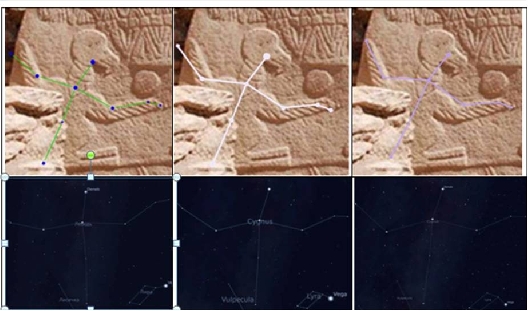

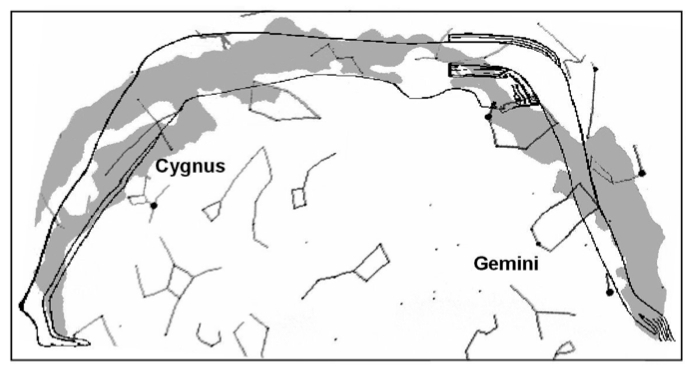

Cygnus as a Vulture If Pillar 43's scorpion does represent the Scorpio constellation, and is thus symbolizing the point of crossing between the ecliptic and the Milky Way's Dark Rift, then the vulture with articulated wings and clown-like feet at the top of the stone completes the cosmic picture. Its wings, head, neck and body have a familiar ring to them, for they form a near perfect outline of the Cygnus constellation, with the vulture's head in the position of Deneb and its outstretched wings matching those of its celestial counterpart. This identification with Cygnus, first noted by Professor Vachagan Vahradyan of the Russian-Armenian (Slavonic) University,(21) is remarkable and unlikely to be coincidence. |

Cygnus overlaid on the vulture shown on Pillar 43 at Göbekli Tepe as done by Professor Vachagan Vahradyan of the Russian-Armenian (Slavonic) University. Pic credit: Vachagan Vahradyan. |

Thus

the abstract imagery on Pillar 43, with its headless matchstick man next to the

scorpion, and the ball-like head above the left wing of the vulture, probably

shows the transmigration of the soul from its terrestrial environment, signified

by the stars of Scorpio, to its final destination in the after life. This, it

would seem, was the sky-world entered via the Milky Way's Dark Rift, marked by

the stars of Cygnus, represented by the stone's vulture with outstretched wings.

Equally, spirits would have been able to travel from the sky-world via the opening

of the Milky Way's Dark Rift via the enclosure's holed stone, bringing forth life

into the world. Arguably, it was similar beliefs that inspired the alignment of

various examples of monumental architecture around the world, which all feature

Cygnus alignments. These include Avebury in England, Newgrange in Ireland's Boyne

Valley, Great Circle in Newark, Ohio, and even the Pyramids of Giza in Egypt.(22)

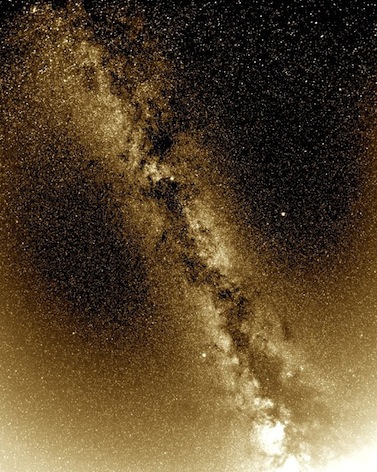

The Milky Way's Dark Rift, with Deneb positioned at its opening. Vega in Lyra is to its right, with Altair in Aquila below. Together these three bright stars form what is known as the Summer Triangle. | Cosmic Birth Almost exactly what we see represented in abstract form on the sighting stone in Göbekli Tepe's Enclosure D is found also on the Venus and Sorcerer panel inside France's Chauvet cave, created by a Paleolithic artist some 32,000-30,000 years ago. Here too the abstract legs of the "Venus" seem to signify the twin streams of the Milky Way either side of the Dark Rift, with the head of a young bovine overlaid upon the position of the womb. This bucranium is likely to represent the Cygnus constellation in its role as the head of a bull calf, which in prehistoric times was seen as an abstract representation of the female womb or uterus complete with its horn-like fallopian tubes. The uncanny likeness between the two is something that our distant ancestors would appear to have realized at a very early stage in human development.(23) We are reminded also of the 3D frescoes from Çatal Höyük showing bulls being born from between the legs of divine females (often with the heads of leopards), and the ancient Egyptian belief that the goddess Hathor, in her role as the Milky Way, gave birth each morning to the sun-god in the form of a bull calf, which was seen to emerge from between twin sycamore trees perhaps signifying the twin streams created by the Dark Rift. |

The cult of Hathor was virtually synonymous with that of Nut, the Egyptian sky-goddess, who was herself a personification the Milky Way, her womb and vulva occupied by the stars of Cygnus.(24)

The ancient Egyptian goddess Nut superimposed on the Milky Way as seen in the Northern Hemisphere. Note that her vulva and womb lie in the vicinity of the opening to the Dark Rift and the stars of Cygnus (after the work of American astronomer R. A. Wells). Pic credit: Andrew Collins/Rodney Hale.

Birth

Chamber

How exactly the entrants to Göbekli Tepe's Enclosure D might have celebrated the act of cosmic birth is open to speculation. Perhaps the soul was seen to emerge from the opening of the Dark Rift, and then in some unimaginable manner enter a pregnant woman waiting between the enclosure's twin pillars. A ritual act like this might have taken place either at the point of conception, sometime during pregnancy or, perhaps, shortly before birth. It might even have been the case that certain births actually took place between the enclosure's central pillars, mimicking exactly what the incised lines on the holed stone were attempting to convey in such a crude and naïve manner.

So

not only were the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe built to honour the departure

of the soul in the company of the vulture, acting in its role as psychopomp (remember,

the Vulture Stone is next door to the holed stone), but they might also have celebrated

the bringing forth of new life from the sky-world. In fact, it is likely that

a psychopomp, in the form of a bird, was thought to accompany new souls entering

this world. This, of course, is the role played in many parts of Europe and Asia

by the stork, although in the Baltic (and seemingly in Siberia (25)) it was a

white swan that played this same role.(26) In its guise as a celestial bird, Cygnus

is identified with the swan throughout the Eurasian continent. |  |

In Egyptian and Hindu myth it was a primordial goose or swan that brought forth the universe with its honk, although in many other countries the swan was said to have laid the egg that either formed the earth or heavens, or became the sun (such as Tündér Ilona, the Hungarian fairy goddess, who laid an egg in the sky that became the sun, "when she was changed into the shape of a swan"(27)).

Cosmological

Beliefs

Everything points towards Enclosure D's holed stone and Vulture Stone next to it being not just confirmation of Deneb's place in the mindset of the Göbekli builders, but also in the site's role as a place where the rites of birth, death and rebirth were celebrated both in its architectural design and in the highly symbolic carved art left behind by its builders. It is confirmation also of the incredible role played by Cygnus and the Milky Way's Dark Rift in the cosmological beliefs of the Upper Paleolithic age and, later, among the early Neolithic peoples of Anatolia. These are incredible revelations that entirely alter our currently held views on the mindset of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world.

Notes

and References

1. Dates based on an extinction

angle of Deneb at two degrees including refraction using Stellarium, and rounded

up or down to the nearest degree.

2. Dietrich, 2010, pp. 82-83.

3. Schmidt

and Dietrich, 2010.

4. Dietrich, 2011.*

5. Ibid.

6. Azimuths are based

on Özdogan and Özdogan, 1989, pp. 65-74, with an extinction angle of

Deneb at two degrees using Stellarium.

7. Yakar, in Steadman and MacMahon,

2011, p. 67, summarizing Bischoff, 2006,* 2007.*

8. Personal conversation between

Klaus Schmidt and the author on September 16th, 2012.

9. Hodder, 2006, p. 196.

10.

Uyanik, 1974, p. 12.

11. Ibid.

12. Klaus Schmidt talking to Dr Graham Philip

on Ancient X-Files, Episode: "Death Cult Temple & Bog Bodies of Ireland",

2012.

13. Solecki and Solecki, in Solecki, Solecki, and Anagnostis, 2004, p.

120.

14. See Solecki, 1977, pp. 42-47.

15. Solecki and Solecki, 2004, p.

120.

16. Solecki, 1977.

17. Solecki and Solecki, 2004, p. 117.

18. Belmonte,

2010, pp. 2052-62.

19. Horowitz, 1998, pp. 156, 180-1, 259; White, 2007, 177-81.

20.

Bricker and Bricker, in Aveni, 1992, pp. 148-183.

21. See Vahradyane and Vahradyane.*

22.

See Collins, 2007; Collins, 2010a;* Collins, 2010b.*

23. Gimbutas, 1989, pp.

185, 265.

24. See Collins, 2007.

25. Silva, 2008, p. 125.

26. Kay, 1898,

p. 197.

27. Róheim, 1954, p. 63.

* an asterix

after an entry denotes it being an internet source

Bibliography

Aveni,

Anthony F., ed., The Sky in Mayan Literature, OUP, 1992. |

The author would like to express his gratitude to Rodney Hale for his essential role in establishing Göbekli Tepe and Çayönü's astronomical alignments, and Greg and Lora Little for their advice and comments. This article comes by way of a prelude to Andrew's upcoming book Finding Eden, published by Inner Traditions (2013). Ancient aliens. ancient astronauts. Graham Hancock. OCT. Giza. Hall of Records. 10,000 BC. Astronomy. Archaeoastronomy. Watchers. Anunnaki. Nibiru. Sitchin. Robert Bauval. Adrian Gilbert. |

The author resting beneath the shade offered by the fig-mulberry tree marking the summit of Göbekli Tepe. |