![]()

![]()

TUTANKHAMUN NOT MURDERED

-

ITS OFFICIAL

Press Release, posted on andrewcollins.com, 9 April 2005

A recent CT Scan survey of King Tut confirms he was not murdered, and instead may have died following a fall from a horse or chariot, linking his untimely demise with a curious story preserved in the Jewish Talmud.

Tutankhamun was not murdered - that's the official line from Egypt's

Supreme Council of Antiquities following a recent CT scan survey of

his remains. In contrast, there is now mounting evidence that the boy

king died following a fall, a theory championed by Egyptological writers

Andrew Collins and Chris Ogilvie-Herald.

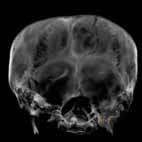

In January, an all-Egyptian team of pathologists, radiologists and anatomists, overseen by Dr. Madiha Khattab, Dean of Medicine at Cairo University, removed the pharaoh's skeleton from its stone sarcophagus in the Valley of the Kings, and used ultra-modern CT scan equipment to take a total of 1,700 pictures.

In the presence of three independent foreign observers, one from Switzerland and two from Italy, the images were scrutinised at length by the all-Egyptian team. Although there were differences of opinion among the scientists, they all agreed on one thing: Tutankhamun did not die from a blow to the head, a theory popularised by those who believe he was murdered, since no evidence of any cranial fractures were found, or indeed any evidence of foul play.

|

A careful examination of the skull cavity did reveal the presence of two loose bone, although these came not from the cranium as some believe, but from the neck (more specifically from the fractured cervical vertebra and foramen magnum). They are thought to have been dislodged by the embalmers during the mummification process, most probably when a second entrance was sought in which to pour the embalming fluid (the nasal cavity was also used for this purpose). |

In addition to this, no trace of the aberration, or 'dark area', first noted at the back of the skull following an x-ray examination of the remains by Professor Ronald Harrison of Liverpool University back in 1968, was seen, further confirming that Tutankhamun did not suffer a blow to the head, or suffer any kind of brain haemorrhage as a result of it. Tutankhamun's skeleton - which reveals that he was slightly built - indicates also that in life he was well fed, healthy and suffered no major childhood malnutrition or infectious diseases.

Another rumour dismissed by the recent CT scan survey is that the boy king suffered from a crippling medical condition. Most favoured is Klippel-Feil syndrome, which results from the congenital fusion of any two of the seven cervical (neck) vertebrae, and will eventually lead to various symptoms of illness including head deformation. It is a theory championed by supporters of the murder solution to Tutankhamun's demise, who felt they had recognised its presence in the boy king from artistic representations of him and his family, the presence of some 130 walking sticks found in his tomb, and a close examination of the 1968 x-rays. In their opinion, a disorder of this type would have caused the young pharaoh to lose grip of the country, resulting in his death at the hands of someone in the royal court.

However, the CT scan found no evidence that the king had a curved spine, even though the upper vertebrae did seem to be out of place. This has been put down to heavy handling of the remains during the autopsy in 1925. Moreover, the Egyptian scientists noted that although the king's cranium is slightly elongated, it is typical of skulls belonging to members of the same family group, who ruled Egypt at the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty, c. 1400-1320 BC.

.jpg) |

Despite these findings, advocates of the murder hypothesis, which include Zahi Hawass (pictured here with Tut's remains as it enters the CT scan), Director General of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, now consider it possible that because the age in which Tutankhamun lived was plagued by religious turmoil and political intrigue the young king could have been poisoned. Yet with speculations concerning Tutankhamun's murder fast fading, another mystery raises its head. The pathologists who examined the CT scan results determined that the king's thigh bone and ribcage were both broken. Since embalming material had seeped inside the thigh wound, and there is no obvious evidence that the bones had started to heal, the Egyptian team admit it is possible that these fractures occurred shortly before death. |

On learning this news, Robert Connolly, Senior Lecturer in Physical Anthropology at Liverpool University's Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology, re-examined the original x-rays from 1968, and admitted that if the breakages did not occur when the body was autopsied in 1925, then it is clear evidence that the young pharaoh might have suffered an accident before death.

In his opinion: 'It's possible Tutankhamun's thigh injury could have been sustained in an accident. There are remarkable similarities between his ribcage injuries and those of a British mummy - St Bees Man in Cumbria - who sustained fatal damage to his chest in a jousting accident. It is therefore highly possible that the king could have died as a result of a chariot or sporting accident, or even at war.'

It is a theory explored by Andrew Collins and Chris Ogilvie-Herald in their book TUTANKHAMUN: THE EXODUS CONSPIRACY (Virgin, 2002). They found support for the idea that the young king fell from a horse or chariot, leading eventually to his death, in a most unlikely source - the Jewish Talmud, the collected folklore of the Jews. Here an unnamed Egyptian pharaoh, equated with the biblical Exodus and identified by the authors as Tutankhamun, is said to have sustained injuries after a fall, and died shortly afterwards.

According to the account, as the king's steed passed into a narrow place on the borders of Egypt, other horses, running rapidly through the pass, 'pressed upon each other until the king's horse fell while he sate upon it, and when it fell, the chariot turned over on his face, and also the horse lay upon him. The king's flesh was torn from him… [and his] servants carried him upon their shoulders ... and placed him on his bed. He knew that his end was come to die, and the queen Alfar'anit and his nobles gathered about his bed, and they wept a great weeping with him.'

Collins and Ogilvie-Herald believe that this account from the Talmud is consistent with the injuries sustained by Tutankhamun shortly before his death. What is more, if correct, it places the ancestors of the Jewish people in Egypt at the time of Tutankhamun's reign, and indicates that they might have preserved a tradition concerning his untimely death for over 3,300 years. Should this theory prove correct, then it reignites the debate over the identity of the Pharaoh of the Exodus, an event which Collins and Ogilvie Herald firmly believe took place around the time of Tutankhamun's reign.

The CT scan survey of Tutankhamun is to feature in the exhibition 'Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs', which is about to open in the United States and hits Britain in the autumn of 2007.

TUTANKHAMUN: THE EXODUS CONSPIRACY by Andrew Collins and Chris Ogilvie Herald can be obtained by clicking here.

Source Links:

'Fractured

leg bone not the end of Tutankhamen mystery', Press Release, 10 March

2005, Liverpool University.

'No

Sign Tutankhamun Murdered But Mystery Unsolved, Reuters', 8 March 2005,

'How

did the boy king die?', Al-Ahram Weekly, 10-16 March 2005.

'King

Tut 'died from broken leg', BBC News, 8 March 2005.

'Scan

reveals King Tut's mysterious injury', The Guardian, 8 March 2005.

'King

Tut CT Scan Answers Questions', DiscoveryChannel.com, 8 March 2005

![]()

![]()