|

|

![]()

Britain's first prehistoric serpent mound to be buried beneath bypass

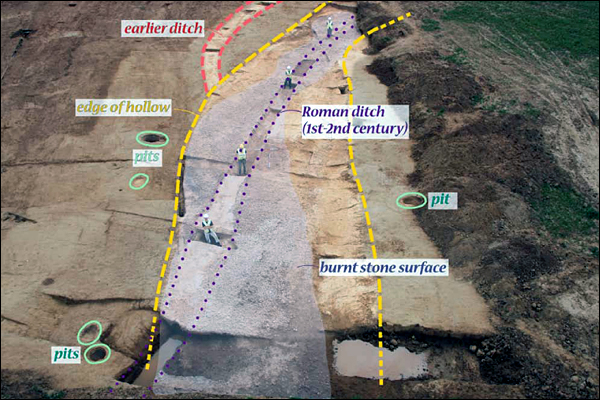

Hereford Council officially released overhead of the Rotherwas Serpent Mound (Pic Credit: AP/Hereford Council)

A Report by Andrew Collins Published: July 7, 2007

LONDON: A Bronze Age

Serpent mound - seen as unique to Europe - has been uncovered by archaeologists

at the site of a new highway.

Excavations at Rotherwas in Herefordshire have revealed a 60-meter (65-yard),

three-dimensional serpentine mound made from piles of fire-cracked stones.

These form a series of linked opposing curves, creating a zigzagging

mosaic pathway that bears striking similarities to a similar mound structure

in Ohio, USA.

The 'Rotherwas Ribbon',

as archaeologists have damply christened it - is orientated roughly

north-south, at right angles to the new road, and has a 'tail-like feature'

at one end.

Herefordshire County

archaeologist Keith Ray, who is leading the excavations, proposes that

the serpentine structure was a ritual centre for the Bronze Age peoples

who inhabited the area some 4,000 years ago.

'It's the only structure

we have from prehistory from Britain or in Europe, as far as we can

tell, that is actually a deliberate construction that uses burnt stones,'

Ray said. 'This is ... going to make us rethink whole chunks of what

we thought we understood about the period.'

Archaeologists believe

that the fire-cracked stones used in the construction of the mound were

created when rocks from a ridge half a mile away were heated in a hearth

and then dropped in water to heat it up.

The use of fire-cracked

stones at Rotherwas is thought to be deliberate, and thus may have ritual

significance.

This is backed up

by the discovery close by of cremated human remains and burnt timbers,

a clear indication of the monument's powerful presence in the landscape.

Henry Chapman of the University of Birmingham, who is working with Dr

Ray in trying to understand the purpose of the serpent mound, adds that

the use of fire-cracked stones could easily have resulted from the desire

to connect aspects of everyday life with ritualistic practices.

'Using domestic waste

in funeral material is very significant in terms of linking life and

death,' Chapman said. 'It's a really neat expression of the psychology

of the period.'

The Rotherwas Serpent Mound is one of the most important discoveries in British archaeology for a very long time. In order to preserve it for future generations detailed plans are being drawn up to encase the site in a protective structure beneath the new road.

THE ROTHERWAS SERPENT MOUND - ITS GREATER IMPLICATIONS

On reading this story,

released by Herefordshire Council with pictures on 4th July 2007, I

was struck by how calm the reports seem to be dealing with the fact

that one of the most unique prehistoric monuments ever found in Britain

is being condemned without mercy to a concrete existence beneath a new

access road.

The term 'preserve it for future generations' is exactly what English

Heritage and the National Trust say about the many megaliths known to

be buried beneath the Avebury henge monument. What this in fact means

is that no one can ever touch them, not now or in the future.

So to put the term

'preserve it for future generations' in plainer terms, it means that

the Rotherwas Serpent Mound will be encased in concrete and tarmac and

quietly forgotten about by all but the most dedicated earth mysteries

enthusiasts. This is a terrible shame, for its existence, not to mention

the site it occupies, offers a unique opportunity to study the religious

beliefs and practices of the Bronze Age mindset some 4,000 years ago.

Remember, Rotherwas is just 85 miles (136 kms) from Avebury, where in

2000 BC serpentine avenues of standing stones were still under construction.

The fact that the

public were not made aware of the discovery of the Rotherwas Serpent

Mound until now, also smacks of the site being kept under raps for fear

of road protesters and eco-warriors occupying the site, and, in the

resulting publicity, forcing a public debate on whether or not the Rotherwas

access road was valid or not. This is a terrible shame, and if at this

advanced stage there is anything anyone can do to save the Rotherwas

Serpent Mound, then please do it.

We shall report again on this matter in due course.

BRITAIN'S OTHER SERPENT MOUND

The Rotherwas Serpent

Mound is being hailed as unique to Europe. However, this might not be

the case, for a serpent mound of very similar age and appearance once

existed close to the banks of Loch Nell (or Loch-a-Neala, meaning 'Lake

of the Swans'), some 3 miles (4 kms) south of Oban on Scotland's west

coast. It was explored in 1871 by Mr JS Phene, FSA, who determined through

excavation that at its western extremity, identified as the serpent's

'head', was a cairn of stones beneath which were 'three large stones

forming a megalithic chamber, which contained burnt bones, charcoal,

and burnt hazel-nuts,' as well as a flint implement.

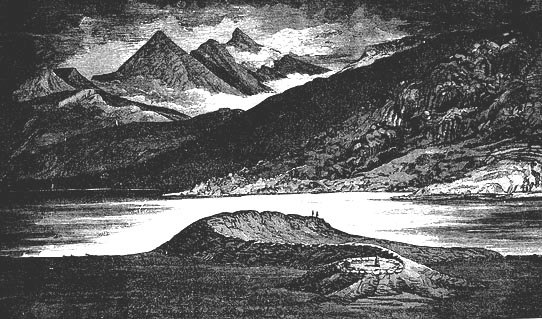

Just one year later the structure was visited by travel writer and painter Constance Gordon Cumming, who gave an account of it in a work entitled Good Words, published in 1872, and again in her book In the Hebrides, published in 1883. In here she describes the monument as 'a huge serpent-shaped mound', as well as 'a very remarkable object, and one, moreover, which rises conspicuously from the flat grassy plain, that stretches for some distance on either side, with scarcely an undulation, save two artificial circular mounds, in one of which lie several large stones, forming a cromlech. These circles are situated a short distance to the south, to the right of the Reptile.'

The Loch Nell Serpent Mound taken from Constance Cumming's In the Hebrides (1883)

Cumming said the structure

was totally artificial, and estimated its size to be around 17 to 20

feet in height and some 300 feet in length. According to her it was

'perfect in anatomical outline', while on its head was a 'circle of

stones, supposed to be emblematic of the solar disc'.

Prior to Mr Phene's

visit in 1871, Cumming recorded that at the centre of the stone circle

were 'some traces of an altar', although this had now disappeared due

to the presence of cattle and herd boys.

Phene, as quoted in Cumming, provided the following account of the serpent's spine:-

On removing the peatmoss and heather from the ridge of the serpent's back, it was found that the whole length of the spine was carefully constructed, with regularly and symmetrically placed stones, at such an angle as to throw off the rain.

Cumming herself described

the spine as 'a long narrow causeway, made of large stones, set like

the vertebrae of some huge animal.' which surely bears some resemblance

to the Rotherwas Serpent Mound, with its own mosaic-like pathway.

She goes on: 'They [the vertebrae] form a ridge, sloping off at each

side, which is continued downward with an arrangement of smaller stones

suggestive of ribs.'

The mound was built

in such a manner that the worshipper standing at the altar 'would naturally

look eastward, directly along the whole length of the Great Reptile,

and across the dark lake, to the triple peaks of Ben Cruachan. This

position must have been carefully selected, as from no other point are

the three peaks visible.'

The Ben Cruachan are

sacred mountains associated in legend with the Cailleach Bheur, the

old hag of the mountains, while the serpent mound itself was once said

to be the burial place of the Scottish folk-hero Ossian, son of Fingal.

The Cailleach Bheur

is considered the dark half of the Irish and British goddess Brigid,

who principal zoomorphic symbols are the serpent and swan, reflecting

he root of loch Nell's name and the presence on its shores of the serpent

mound.

The Loch Nell Serpent

Mound, with its cairn, stone-lined cist and cremated remains, appears

to date back to a similar age as the Rotherwas Serpent Mound, ie. to

the Early Bronze Age, c. 2000 BC. Thus a relationship might exist between

the two cultures responsible for these prehistoric monuments hundreds

of miles apart.

It might pay the archaeologists

working currently at Rotherwas to visit Loch Nell to study the environment

and topography behind the siting of such monuments.

Today the Loch Nell serpent mound is in a ruinous condition, although the cairn at its head, as well as the undulating ribbing of piled stones, are still partially visible.

COMPARISONS WITH OHIO'S

SERPENT MOUND

Regarding the comparisons

with Ohio's own Serpent Mound, located in Serpent Mound Park, Adams

County, the matter becomes that much more tricky, even though the similarities

between the two are striking to say the least.

They include the fact that an oval shaped mound held in the jaws of

the serpent's head once possessed a mound of stones, according to the

ethnologist Frederic Ward Putnam, who investigated the site back in

1890. According to him:

|

Ohio Serpent Mound from above. |

Many of the stones show signs of fire, and under the cliff are similar burnt stones which were probably taken from the mound years ago; for I have been informed by an old gentleman, who remembered the stone mound as it was in his boyhood, that many stones taken from the mound were thrown over the cliff (Putnam, The Serpent Mound of Ohio, 1890. |

Dr Keith Ray, the

Herefordshire Council archaeologist in charge of the excavations at

Rotherwas, has made it clear that he does not believe there is any historical

or cultural link between the two serpent mounds, which were built over

3000 years apart. Despite this the similaries cannot be overlooked,

and should be examined without prejudice.

![]()

|

|